The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2022 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

The essay’s author Thi Hoang is an analyst at the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) and the managing editor of the Journal of Illicit Economies and Development (JIED). The author thanks Nicole Kalczynski for her great support in conducting the literature review for this essay.

Mixed migration and human trafficking are closely intertwined. While the causal relationships between the two phenomena vary in line with the intent of the parties concerned and the precise role of any traffickers or smugglers involved at a given point in time, two broad—and overlapping— dynamics can be postulated: migration-led human trafficking, and trafficking-led migration.

Introduction

There are many inter-related threads to the connections between mixed migration and human trafficking. These include: geography, because the two often occur in the same location or along the same routes; power disparities, because refugees and migrants, being far from home and often dependent on smugglers, frequently find themselves in situations of vulnerability to exploitation; money, especially in cases where this runs out en route or when those on the move chose a travel-now-pay- later arrangement with smugglers; and knowledge, in the sense that people travelling generally know much less about their surroundings and border formalities than those they pay to facilitate their journeys.

To help untangle all this complexity and shed light on its inherent causal relationships, this essay proposes the concepts of migration-led human trafficking, and trafficking-led migration.

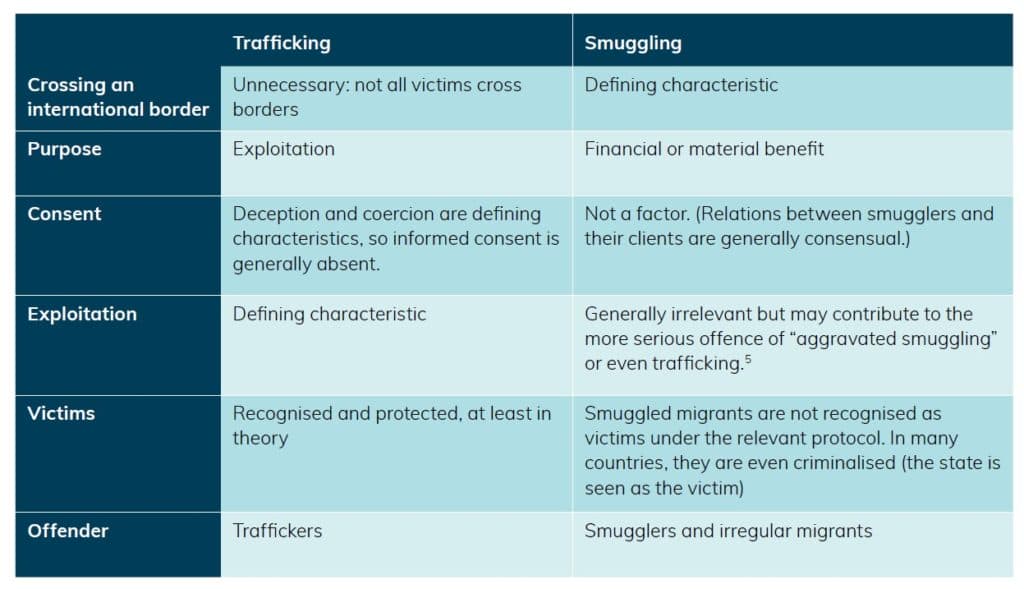

Before exploring these two concepts in detail, it is worth briefly revisiting the distinctions between trafficking and smuggling, which although set out in international law, are often lost in media coverage or deliberately conflated in political rhetoric designed to fuel anti-migration sentiment or distract voters from more factful (if unpopular) discussions of mixed migration issues. As a result of this conflation, many victims of trafficking are not identified as such by state authorities and are thus denied the protection they deserve, or even treated as criminals for having migrated irregularly.

What emerges from these distinctions is the overriding importance of intent, or, more specifically, whether an intention to exploit through the use of threats, violence, deception or other forms of coercion, was at any point a factor in the facilitation of a migrant or refugee’s journey.

Migration-led human trafficking

This form of trafficking occurs during or after a migration journey. It may result from smugglers initially hired as service providers morphing into outright exploiters or, as in the case of Eritreans fleeing their country to neighbouring Sudan, being sold by smugglers and even Sudanese state officials to traffickers who then take them into the Sinai in Egypt to be handed over to other trafficking and extortionist groups.

Human trafficking vs. migrant smuggling: what the law says

Source: Adapted from United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime

Migration-led trafficking is more common in relatively low-cost smuggling arrangements in which those on the move either pay as they go at different points on their journey, or “travel now, pay later.” While these models obviate large up-front payments, they are not without risk, and are among the factors that contribute to migration journeys degenerating into situations of trafficking. These include:

- aggravations along the routes, such as the Covid-19 pandemic and the resulting closures of—or increased security at—borders which left many refugees and migrants stranded mid-journey, facing increased costs for smuggler services (accommodation, food, drink, personal hygiene, etc) and thus more indebted to their smugglers and obliged to offer their labour and/or sexual services to settle their dues;

- smugglers changing roles, from providing a range of services to refugees and migrants on a willing-buyer willing-seller (or even pro bono) basis, to more abusive or exploitative activities, as a result of greed, financial hardship, sexual gratification, or threats from other criminal actors;

- stringent migration policy and border security measures that increase the costs of smuggling operations, sometimes prompting those involved to turn to more nefarious activities such as kidnap-for ransom, as reported in Libya;

- onerous debts resulting from payment modalities such as “travel now, pay later”, or “pay-as-you-go” which may oblige smugglers’ clients to engage in exploitative labour and/or sex work; and

- challenges in destination countries, including unemployment or lack of employment opportunities; discrimination; linguistic barriers; lack of understanding of local laws, customs, and labour rights; lack of social safety net protection and welfare support; and pandemic-related economic downturns and lockdowns that especially impacted low-skilled and/or informal sectors such as hospitality, construction, and agriculture in which migrant workers make up much of the labour force (e.g. Vietnamese nationals working in restaurants and nail salons in France and Germany and Ukrainian and Romanian agricultural labourers in Italy.). Lockdowns deprived many migrant workers—who often still owed money to their smugglers—of a regular income, pushing them to turn to trading in criminally-controlled sectors such as counterfeit goods, black market tobacco, and illegal drugs, while exposing them to sexual and/or labour exploitation by their creditors.

Migration-led trafficking on the Ethiopia-Yemen route

For the last two decades the number of Ethiopians who have sought to work in Saudi Arabia has been rising and involves hundreds of thousands of people. Some go through government-registered employment agencies and fly there, while others take the irregular and dangerous journey overland and by sea. Every year, more than 100,000 people on average attempt the irregular Ethiopia-Yemen- Saudi Arabia route, pushed by poverty in Ethiopia and hopes of higher salary in Saudi Arabia. Apart from the much-reported abuses and harsh deportations that Ethiopians experience when working regularly or irregularly inside Saudi Arabia, many of those who travel irregularly fall victim to highly abusive smuggling and trafficking practices in Ethiopia itself, as well as in Djibouti and parts of Somalia (such as Puntland) and, especially, in Yemen. This is an extreme and consistently brutal example of migration-led human trafficking where Ethiopian men, women, and children face robbery, kidnapping, sexual violence, exploitation and, very frequently, extortion from gangs demanding ransom at every step of the way, thereby becoming de facto victims of trafficking soon after their migration journeys start. Often, they face repeated detention along the route, and for women and girls the level of sexual abuse is extremely high. In lawless and war-torn Yemen, Ethiopians face the greatest risks: deaths are not uncommon from malicious smugglers and traffickers who often sell migrants on to other gangs along the route. The full extent of forced detention, abduction and trafficking in Yemen remains unexplored.

Human trafficking-led migration

Migration results from trafficking activities when victims are transported across national borders for purposes such as labour exploitation, sexual exploitation, slavery, servitude, or the removal of organs, as defined in the Palermo Protocol.

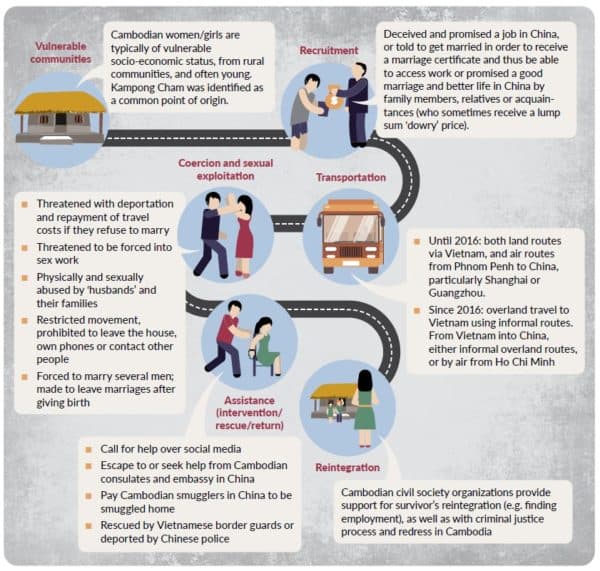

Globalisation has transformed the movement of not only goods and materials, but also people worldwide. Criminal actors engaged in human trafficking have been capitalising on this development, transporting people from regions with lower labour costs or from vulnerable communities to places with high demand for cheap labour. In some cases, victims of such actors may be aware from the outset—because of the use of violence, coercion, threats, or close surveillance, etc—that they are being trafficked and even that they will be taken across borders for the purposes of exploitation, such as sex work, unpaid or poorly paid labour, or forced marriage. In other situations, victims might only find out that they are being trafficked en route or after they have reached the destination country. This is what often happens to Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Burmese women and girls lured to China under the false promises of a well-paid job or a consensually arranged marriage to a wealthy man. These women and girls usually enter China on a one-month tourist visa, with their travel expenses often paid upfront by traffickers. Marriage may—again falsely—be presented as a necessary condition for employment in China. If victims then refuse to proceed with the marriage they may face threats of violence, or of their irregular status being denounced to authorities, or be ordered to immediately pay back travel expenses and dowry fees in return for their freedom.

Forced marriage recruitment strategies targeting Cambodian women and girls

Gratefully reproduced from Chhun, V. et al Cambodia’s trafficked brides: The escalating phenomenon of forced marriage in China.

One group that is particularly affected by trafficking-led migration is Myanmar’s Rohingya, who are frequently trafficked from refugee camps in Bangladesh and from Myanmar’s Rakhine state. Lured under false pretenses by traffickers touting promises of steady employment, or falling victim to exploitation when seeking to escape the deteriorating conditions of refugee camps, Rohingya, including refugees, are trafficked into countries such as Malaysia. Southern Thailand is a main transit point from Myanmar to Malaysia and Indonesia, and functions as a shelter for traffickers engaged in transporting Rohingya to neighboring destinations. The traffickers are part of organised syndicates whose profits wield influence over local officials throughout the region. Reports have indicated that a number of Rohingya refugees have been killed, subjected to sexual assault, raped, and tortured by traffickers, while many others have drowned at sea. Meanwhile, in Rakhine state, women are recruited into (forced) marriage to Rohingya men in Malaysia, and en route risked being stranded at sea or held in jungle camps on the Thai-Malaysian border, where traffickers would demand a US$1200-2000 fee to let them continue their journey. If they were unable to pay the required amount, armed traffickers held them in captivity on board vessels or in the jungle camps, without providing basic necessities like water and food. In this setting, women were at a higher risk of sexual- and gender-based violence, and many ultimately ended up in forced marriages or at sex markets where they were sold for higher prices.

Labour exportation schemes

Trafficking-led migration may entail “labour exportation” programmes in which traffickers pose as legitimate recruitment agents (or similar kind of intermediaries) offering job opportunities abroad in low-skilled sectors such as domestic service, agriculture, or construction to people in communities that are rural, marginalised, and poor. Again, victims of such practices only discover they are in a situation of trafficking upon or after arrival, when, for example, their documentation is confiscated; or their salary is not paid in time or is much lower than promised; or they are forced to work much longer hours than stipulated in their contracts, often with unpaid overtime; or their working and living conditions are much worse than expected; or they are prevented from leaving.

Such exploitative practices are not the exclusive domain of criminal organisations: sometimes legitimate companies and state-connected actors have been complicit. Examples include: the forced labour of Vietnamese migrant workers recruited through labour exportation programmes to work in a Chinese-run tyre factory in Serbia and US government contractors allegedly abusing tens of thousands of low-skilled migrants, mostly from India, Nepal, the Philippines, and Uganda, providing construction, security, catering, and food services to US military and diplomatic missions in Iraq and Afghanistan. Members of this “army behind the army” were paid as little as $150–275 per month (far less than the promised $1,000), forbidden to leave or return home, and housed in dangerous, unsanitary, and degrading conditions. Moreover, many were charged recruitment fees ranging between $1,000 and $5,000, which led them to resort to loan sharks (with annual interest rates as high as 50 percent), placing them in a situation of debt bondage. In many cases, the abused and exploited workers had also been told they were heading to Dubai, Kuwait, or other Gulf States, only to find out too late that they would be working in a conflict-ridden Afghanistan and Iraq. Some were even reportedly kidnapped and executed by insurgents while travelling to their workplace.

Other examples of trafficking-led migration include cross-border organ trafficking; cross-border surrogacy (e.g. Cambodian women travelling to Vietnam to give birth and deliver babies to Chinese nationals); foreign prisoners in situations of forced labour; children taken across borders and obliged to beg (e.g. Roma children in Central and Eastern European countries); and the forced recruitment of child soldiers for combat overseas (e.g. Afghan children coerced into fighting alongside the Shia militias in Syria by both the Iranian government and the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps).

Birds of a feather

The smugglers and traffickers involved in both migration-led trafficking and trafficking-led migration operate along similar migration routes, and sometimes even collaborate in transporting people on different legs of the journey. Many smugglers and traffickers have social and economic backgrounds similar to each other’s and those of their clients/victims: most come from rural, poor, and marginalised communities or villages. Smugglers and traffickers also share modus operandi, in that both groups take advantage of vulnerable communities and their desperate—or even life-threatening—situations and of the power and knowledge imbalances between them and their clients/victims. Some organised criminal groups reportedly engage in both smuggling and trafficking. Other smuggling and trafficking groups were found to converge at locations such as tourist hotspots in the Western Balkans and Sihanoukville in Cambodia, where thousands of Vietnamese, Laotian, Thai, Chinese, Indian, and Ukrainian young people have been imprisoned and forced to operate sophisticated cyber scams in Chinese-run casinos, to where they were taken with false promises of high-paying jobs in online trading.

Case study: Afghanistan

Afghanistan offers examples of both migration-led trafficking and trafficking-led migration, as well as of overlaps between the two.

In 2021, more than 2.7 million people from Afghanistan were refugees, a number only surpassed by those from Syria (6.8 million). The scale of internal and cross-border displacement of Afghans has been steadily rising since 2016. In 2021, about 15 percent of Afghanistan’s population, some 6 million people, were displaced internally and across borders.

Having lost their homes, livelihoods, and social contacts such people are particularly susceptible to negative forms of survival, subsequently putting themselves at risk of trafficking. These risky strategies may include embarking on unsafe journeys, selling their organs, offering sexual services, agreeing to exploitative labour conditions, or in some cases, forcing their daughters or sons into marriage and/or being sexual partners of wealthy and powerful individuals as a means to acquire the financial means for the family’s survival, and/or to offset the migration costs.

Given their dire situations—encompassing the effects of several years of extreme drought, an economic crisis worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic, and the insecurities and uncertainties brought about by a Taliban-led government—an increasing number of Afghans have tried to seek a new life and job opportunities overseas, mainly in Iran, Pakistan, Türkiye, the Gulf States, and Europe. Capitalising on this need, many traffickers, disguised as labour intermediaries and recruiting agents, have offered them false employment in low-skilled sectors such as domestic work, construction, and agriculture. Once they arrive, many Afghan migrants and refugees are then threatened and forced into trafficking situations of labour and sexual exploitation. Specifically, Afghan women and girls are exploited in sexual and domestic servitude in Iran, India, and Pakistan, whereas the men and boys have been trapped in forced and bonded labour in the construction and agricultural sectors in Greece, Türkiye, the Gulf States, Iran, and Pakistan. Afghan children have also been exploited in criminal activities such as smuggling drugs, fuel, and tobacco, and as street beggars and vendors, in Iran and by Iranian criminal groups. When apprehended, these children risk being detained, tortured, and extorted by the Iranian police. Furthermore, Afghan children have also been coerced into fighting alongside the Shia militias in Syria by both the Iranian government and the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps.

Afghan migrants and refugees residing in Iran have also been trafficked into Europe by criminal groups for bonded labour (e.g. working in restaurants) and forced sex work, to pay off their smuggling debts. Media and grey literature reports have also documented cases of Afghan boys being forced to become bacha bazi in Germany, Austria, Sweden, Finland, Hungary, Macedonia, and Serbia.

In addition to Afghan migrants and refugees being specifically targeted by traffickers overseas, criminal groups have reportedly preyed on Afghan returnees or those deported from Iran, Pakistan, Türkiye, and European countries over the last five years. Many Afghan returnees have been trafficked into labour exploitation in agriculture, brickmaking, and carpet weaving. Within this essay’s conceptual framework, this phenomenon could be termed “return migration-led trafficking”. Against this backdrop, many NGOs and civil society actors, such as Amnesty International, issued public statements calling on European countries to stop deporting Afghan refugees and migrants back to the dire and life-threatening situations in Afghanistan.

Which way forward?

One of the first steps moving forward is to change the current framing and narratives of the migration- trafficking discourse. By changing the narratives, or exploring the issue from multiple lenses and perspectives, stakeholders, and the general public will better understand the nuances of the issue and the overlaps and interconnections between mixed migration, smuggling, and trafficking.

More nuanced narratives will also help counter the common conflation of smuggling and trafficking. A failure to do this will only reinforce the agendas of certain political and economic actors, increase the vulnerability to trafficking of many refugees and migrants, prevent many trafficking victims from being identified and adequately supported, and allow law enforcement agencies to continue focussing on smugglers rather than the more harmful traffickers, who will continue to benefit from the extensive impunity they enjoy in most regions in collusion with state actors. Not only do states fail to adequately censure and interdict human trafficking within their own borders, but they often put minimal or negligible effort into protecting their own citizens abroad who systematically become victims of trafficking.

Fulfilling one of the central ambitions of both the Global Compact for Migration and the EU’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum, namely, to increase the scale and scope of legal migration globally, could well reduce the prevalence of migration-led trafficking, but would probably have less impact on trafficking-led migration. Another step forward would be to further explore why smugglers become traffickers or practice “aggravated smuggling”. Is it simply because at some point they realise there is more money to be made out of exploiting refugees and migrants, instead of only transporting them for a fee? Or is there something else that pushes smugglers along certain routes and in certain countries to start engaging in such violent and exploitative behaviour? Additionally, the sector needs to research why some migration routes are more susceptible to trafficking and abuse than others. What determines vulnerability to trafficking?

This essay has highlighted the interconnections between mixed migration, migrant smuggling, and human trafficking. Given their intersections and overlaps, the root causes of mixed migration, migrant smuggling, and human trafficking (or vulnerability to trafficking) also interweave: many migrants and trafficking victims migrate, or become subject to being trafficked and exploited, because of poverty, armed conflict, financial hardship, and statelessness, or because they come from marginalised and/or persecuted communities. Therefore, only by addressing these root causes and prioritising them over approaches which merely address symptoms, such as increasing border security measures, enhancing policing, and criminalising smugglers or low-level traffickers, and by raising public awareness, will we be able to get to grips with the connections and overlaps between mixed migration, migrant smuggling, and human trafficking, and mitigate their attendant human sufferings and injustices.