The following article was originally compiled for the Quarterly Mixed Migration Update, Europe, Quarter 2, 2024 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

All the European political groupings in the parliament have placed migration management among the most urgent priorities for the next legislature, with the New Pact on Migration and Asylum at the centre of the debate: the European Parliament election results will therefore have a direct impact on mixed migration in Europe. The EU elections that took place between 6 to 9 June 2024 did not bring the anticipated overwhelming win for the far-right. However, the overall success of right-wing parties was unprecedented and further normalises previously marginalised far-right groups. The EU’s stance and discourse on migration have become much tougher, and several mainstream parties have adopted more restrictive immigration policies. The salience of immigration in national and EU-level politics is significant, rising and influencing outcomes. The accompanying politicisation of migration is arguably only matched by its divisiveness in politics. Overall, the right will now pack a heavier punch in the EU immigration debate.

Main EU election outcomes

MEPs from 27 countries fought for 720 seats. Whatever their party affiliation in individual countries, once elected to the EU Parliament most MEPs are linked to specific groupings representing their political and ideological position.

The three immediate outcomes of the June elections are:

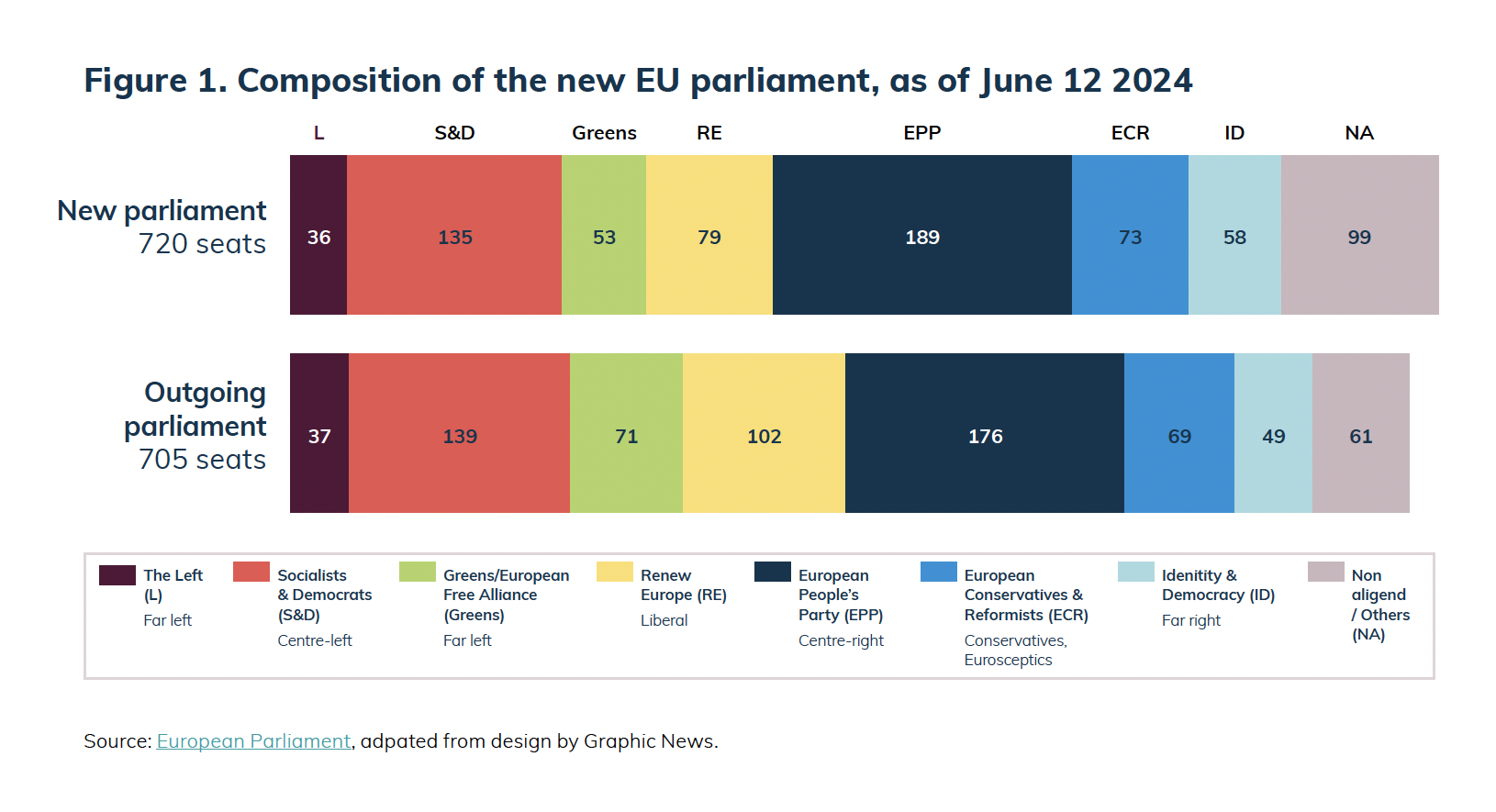

• First, the centre-right has consolidated its position as the largest political grouping in Europe – a continuation of the dominance of the European People’s Party (EPP) with significant support from the European Conservatives and Reformists Party (ECR Party).

• Second, the Greens and the Liberals (Renew Party) saw their power shrinking significantly – the Greens lost more than 25 per cent of their seats and the Liberals 22 per cent. Meanwhile the centre-left Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) held on to its position as the second strongest bloc in the parliament with 135 seats, but lost four seats.

• Third, the radical right has continued to strengthen its position gaining more seats (mainly in the Identity and Democracy group with some non-aligned MEPs), along with the conservative centre-right EPP and ECR, as mentioned.

This third outcome is important not only because it represents additional far-right heft in the EU Parliament going forward, but their victories (winning 58 seats, representing 8.1% of total seats) have more seismic political significance in their home countries.

Overall, the EU-wide rightward shift in recent years cannot be denied, gaining deeper traction in the EU elections and looks set to have further gains ahead. Some analysis, looking at the rising popularity of the right among European youth, wonders if the right wave will be sustained as these voters get older and their views become entrenched as mainstream politics – if it hasn’t already done so.

The far right’s mixed success and migration politics in Europe

The far-right with explicit anti-migrant agendas emerged as clear victors in Italy, Austria, France, and registered best-ever results in Germany and the Netherlands. However, although still scoring well – compared to some predictions – the far right failed to gain the support they expected in Hungary, Sweden, Finland, Belgium and Portugal, resulting in the far-right surge being uneven and nuanced.

Analysts consider that the extent of the impact of the European Parliament’s rightward acceleration will depend on whether the relevant parties can unify and work together. In this light, the future development of the new far-right alliances, the Patriots for Europe, established by Viktor Orban, largely replacing the Identity & Democracy group, and the Europe of Sovereign Nations, led by Germany’s far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), should be closely monitored.

It will also depend on the willingness of the centre groups to engage with parties to their right (instead of the left) and thereby capitalise on their collective weight in parliament. Some are reluctant to do so, but these outcomes are also occurring in a context where the left-of-centre parties have already been moving to the right on migration issues, in an attempt to counter the influence of right-wing propaganda and reduce support for far-right parties (even if this strategy already seems to have backfired in a few European elections).

In any case, there remains a significant opportunity to influence the new commissioners—not only through the far right but also through the influence the left may still wield, particularly during commissioner candidate hearings. Commissioners will need the votes of the Socialists & Democrats (S&D), to be confirmed and will therefore need to accommodate some of their key demands. Well-positioned members from S&D, Liberals, or Greens could still make a considerable impact, and the current lack of a cohesive front on the right could also affect their influence on specific policy areas.

Migration and voter concerns

In 2023, 380,000 irregular border crossings were registered, half of them through the Central Mediterranean route. Asylum applications in the EU reached a seven-year high, with over 1.1 million people applying for asylum, nearing the levels seen during the 2015 so-called “refugee crisis”. Meanwhile, a bit less than six million refugees from Ukraine were recorded in Europe as of June 2024.

Ahead of the elections to the European Parliament, a study by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) indicated that migration is not the primary concern for most voters. The 11-country survey highlights that different voter groups are impacted by various crises in different ways – only in Germany does it stand out as the most significant for everyday life. Another study suggests that it is socioeconomic factors over xenophobia that determine the shift to the right. Support for the welcoming of refugees fleeing Ukraine remains strong. According to the results of August 2023 Eurobarometer survey, 79% of people are in favour of welcoming people fleeing the war to the EU. However, a March 2024 Euronews / Ipsos poll of almost 26,000 respondents across 18 member states indicated that 51 per cent had a negative assessment of the EU’s efforts to control its borders. The survey found that 71 per cent of respondents agreed that strengthening border controls to combat irregular migration should be the main focus in the coming years.

The issue of where voters obtain their information and how they form their views in this age of social media and the high politicisation of migration issues is highly relevant, but beyond the scope of this article. Poll results emphasise that migration remains a key policy concern, among other issues, for voters in the EU. However, how incoming policies will address and alleviate these concerns remains to beseen.

Manifestos and mixed migration implications

It is well-documented how the EU as a whole – and certain individual nations, have been engaged in increasingly hard-line immigration and asylum policies and practices. Even without the far-right holding more power, the EU, under the leadership of the EPP, has already implemented many policies which could be considered ‘extreme’ . An ever-mounting number of reports from INGOs, human rights agencies, UN agencies and government investigations catalogue the extent of the EU’s direct and indirect role in practices and policies that not uncommonly result in violations, sometimes lethally.

The direction of travel regarding the EU’s approach to immigration and asylum illustrates that for some years, at the EU parliament and council, the centre-right, conservative and far-right parties (EPP, ECR and ID, see below) have wielded strong influence. All three right-leaning political groups have been strengthened by the June elections bringing their total number of seats to 315. However, 361 votes are needed for a parliamentary majority so the collective right will still need to firstly unite and secondly convince others such as non-aligned MEPs to join them on particular issues going forward.

The manifestos of party groupings at the EU parliament on immigration and asylum conform to expectations – moving along the continuum from moderate and inclusive Greens and far-left to exclusionary and hard-line on the far-right.

The consensus is that the EPP as the largest grouping in the Parliament with 189 seats has retained hold of the middle ground while holding the far right at bay. As mentioned above already under the previous EPP legislation the approach to migration management has been marked by increasingly hard-line policies. Their manifesto for the election was in line with this hardening approach: the EPP are dedicated to strengthening external borders and wants ‘rigorous’ screening of all irregular arrivals and ‘comprehensive’ electronic monitoring at all entry points. They want to hugely increase the staffing and budget of Frontex and implement the transfer of asylum seekers to ‘safe’ countries and thereby process their applications outside the bloc. They also intend to continue using trade, development and visa policies as leverage to force countries of origin to take forced ‘returnees’ deported from Europe or other transit countries. This represents an unapologetic reinforcement and expansion of the same policies promoted by the right in the EU in recent years and to some extent characterise the New Pact on Migration and Asylum.

The ERC echoes most of the EPP positions with even more emphasis on outsourcing asylum applications and border externalisation to outside the EU, controlling the borders and reinforcing Frontex’s and Interpol’s role in protecting borders as well as developing an EU naval mission to ‘block illegal departures’, rather than to save migrants in distress.

The ID grouping have an on-line statute declaration but did not offer a collective manifesto during the recent election. But there are indications at the national level of policies yet more draconian than those promoted by the EPP and ERC. This group includes eleven far-right parties presently.[1] In the absence of an EU-level manifesto explaining their positions, the kind of policies and legislation they will be expected to support as MEPs can be deduced from their national-level manifestos. For example, France’s National Rally (RN) intends to use ‘emergency legislation’ to severely cut both regular and irregular immigration to “stop the flood of immigrants”, and to abolish the “droit du sol” (jus soli) path to citizenship. They intend to toughen conditions for family reunification and replace state medical aid for undocumented immigrants with a fund that would cover only life-threatening emergencies. These proposed changes would be accompanied by a policy of national preference, giving French citizens priority access to housing and jobs, with welfare benefits limited to French nationals. The Netherlands’ Party for Freedom (PVV) and winner of the November 2023 Dutch elections, also wants to use a temporary crisis law to implement the “strictest asylum policy ever” including the rejection of all new asylum claims, the deportation of dual-national criminals and opting out of certain EU migration rules along with a raft of other anti-migrant and anti-Muslim regulations.

However, manifesto declarations are often unachievable, as the PVV found when it formed a coalition government in the Netherlands. Arguably, if the RN in France tried to implement some of their manifesto aims not only could they get bogged down in legal challenges but they could lead to unrest and insecurity – as President Macron has suggested.

Meanwhile, on the other political divide, the well-represented left (S&D), the far-left (The Left) and greens (Greens/Europe Free Alliance) to different degrees propose the mirror opposite of the right. Inter alia, these include some arguing for the dissolution of the New Pact (although not S&D, they supported it); the dissolution of Frontex and migrant detention facilities; the expansion of legal visa access to Europe; the regularisation of existing irregular migrants in Europe and the end of migration deals with ‘dirty’ regimes abroad – a mainstay of the current externalisation policy.

Focus on the new Pact on Migration and Asylum

Apart from their manifesto aims, the most immediate low-hanging fruit of the EPP will be to advance the operationalisation of the regulations contained in the four pillars of the recently passed and controversial New Pact on Migration and Asylum.[2] It must be fully enacted by June 2026, so given the strong views all parties have on the Pact it can also be expected to be the centre of all migration debates in the immediate future. Not least because its elements cover all aspects of migration and asylum policy response and management.

In an effort to enforce coherence, the EU has indicated that member states failing to implement the reforms or being uncooperative to the “mandatory solidarity” and distribution relocation (of refugees) mechanism, could face legal action. Despite conservative and far-right general support for the New Pact, for some, it does not go far enough, or concepts like mandatory solidarity and relocation quotas are unacceptable. For example, the ERC manifesto opposes the forced ‘solidarity’ stating that member states must not force “their citizens to welcome illegal immigrants without their consent”.

In this context, the re-election of Ursula von der Leyen as President of the European Commission is significant. In her speech to the European Parliament, and also outlined in the document setting out her vision, von der Leyen framed migration through a security lens. She announced plans to triple the number of Frontex officers, enhancing Europol’s capabilities, and new measures to curb migration from the Mediterranean region and propose a new approach for returning migrants. Von der Leyen’s second term signals a continuation of stringent migration policies.

The New Pact and other immigration-related issues will no doubt face political resistance, horse-trading and compromise as the 720 MEPs and the Council get down to business in the coming 5 years. But the fact that the New Pact is already in place will give the EU an important platform to start implementing migration and asylum reforms that mostly reflect right-wing, exclusionary approaches. The fact that it was also in place before the election may have the effect of not allowing the right (predicted to make gains) to have pushed for an even harsher Pact, although there is scope now for the individual instruments to be toughened as they come into force. Céline Mias, Director of the DRC Europe Bruxelles Representation, emphasizes the potential for more balanced policy outcomes within the European Parliament, despite its shift to the right:

“While it is true that even the left is adopting a harder line on migration, some parties and MEPs remain committed to social justice and human rights, and they could play an important balancing role. For instance, as the Socialists and Democrats (S&D) and Greens voted to renew EPP-affiliated Ursula Von der Leyen’s mandate as President of the European Commission, she will now be required to make some political concessions to them. Much will now depend on how the groups to the left position themselves during the European Commissioner hearings in September, which could influence the EU’s approach to the implementation of the Pact.”

Much could depend on what individual countries implement and initiate as a de facto interpretation of certain elements of the pact. For example, the ECR group in which Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia party is dominant, supports the idea of outsourcing mixed migration issues. Italy’s deal with Albania in 2023, in which some migrants will be taken to Albanian centres to have their asylum claims assessed, is an example of the kind of outsourcing this group might push for. The New Pact includes potential options for outsourcing so with Italy as part of the ECR group already using their Albania deals as an implementation of an aspect of the Pact they create a precedent and even a standard that others may not be able to fight if presented as a fait accompli.

Immediately after winning EU seats in Austria, its Freedom Party (FPÖ) lost no time in advocating for the far right concept of “remigration” calling its government to name a dedicated EU commissioner. This illustrates that going forward, as the far-right gain strength at home and in the EU a mutually reinforcing relationship may develop with clear negative implications for mixed migration in the bloc. Speculatively, we may also expect the language used around migration and asylum to be, if possible, even less inhibited as the powerful right take their gloves off – exemplifying the further slippage into the normalisation of the extreme.

The wider EU ecosystem

The election results of the 2024 EU parliament are, of course, a reflection of domestic politics of the 27 member states.

With the right and far-right having strengthened their political positions and some in leadership roles across Europe, it would be fair to expect that their influence and the subsequent normalising of the extreme in relation to immigration and asylum are set to be further consolidated. Even more so knowing that previously centrist or social democratic parties (even leftist in Denmark) increasingly adopted “rightist” immigration policies in recent years.

On the other hand, the UK-Rwanda migration deal, which was seen as playing a pioneering role in the outsourcing of asylum processing by other parties in Europe, was scrapped within hours following an electoral result, after years of negotiations, hours of parliamentary discussion, several legal challenges, and rulings and an investment of hundreds of millions of pounds. This shows that the wind can also change quickly in the direction of a more progressive approach to migration. Further, the snap elections in France opened a phase of uncertainty after the election concluded without a clear winner, with the far right finishing in third place, despite initial projections claiming the Front National would emerge in first place.

The resulting picture is therefore quite mixed at this point. However, when the bar has been lowered, and hard-line policies become normalised, reversing them and raising the bar again might be increasingly challenging. In the EU, as mentioned, many hardline immigration and asylum policies have been normalised, some of which have crystallised in the new Pact on Migration and Asylum, making them very hard to redress.

This comes at a time of unprecedented internal displacement and rising numbers of international displacement, with climate change as a threat multiplier, all while advanced economies are in high need of migrant labour. Therefore, the stakes could not be higher, for both vulnerable refugees and migrants as well as European societies.

—

[1] Austria: Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ); Belgium: Flemish Interest (VB); Czech Republic: Freedom and Direct Democracy (SPD); Estonia: Conservative People’s Party of Estonia (EKRE); France: National Rally (RN); Italy: League (Lega); Netherlands: Party for Freedom (PVV); Portugal: Enough!(Chega CH); Slovakia: Slovak National Party (SNS). Germany’s Alternative for Germany (AfD) party was expelled from the ID group in May 2024.

[2] These include detailed regulations under the 4 broad categories of Secure external borders; Fast and efficient procedures; Effective system of solidarity and responsibility and Embedding migration in international partnerships. The various associated legislative files can be found here.