Just paper tigers? The rise and fall of nationalist, populist anti-migrant politics and the mainstreaming of restrictionist policies

The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2021 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

The essay’s author Chris Horwood is a migration specialist and co-director of Ravenstone Consult.

What happened to the anti-migrant and anti-refugee activists and accompanying populist political entities that seemed to be so prevalent between 2015 and 2019 in Europe and beyond? Were they just paper tigers in the end, with no sustainability or teeth? Was it just political opportunism, using nationalist and nativist rhetoric to scapegoat migrants and asylum seekers, or is this still a political force to be reckoned with?

This essay argues that overall and irrespective of the fate of the parties most associated with anti-migrant policies and rhetoric—some of which have since become stronger, others weaker—attitudes towards migrants and asylum seekers have demonstrably hardened. More significantly perhaps, anti-migrant positions and policies have been mainstreamed and adopted by centrist, moderate and even leftist parties.[1]

Power-shifts in Europe

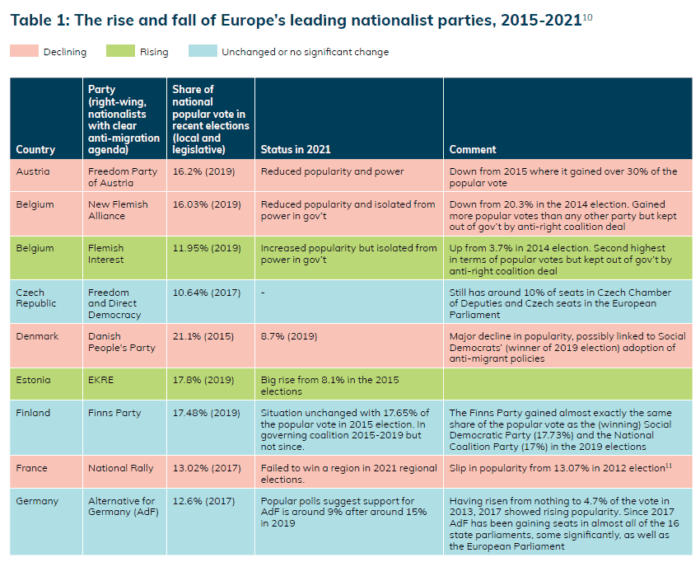

One way to measure the changing power dynamics in Europe is to look at the domestic strength of national political parties with prominent anti-immigration agendas in addition to their presence in the European Parliament.[2] We find some indicative trends if we study parties that achieved eight percent or more of the popular vote in the last five years or so and make a comparison with their position today. Table 1 below shows that trends are uneven and heterogeneous across Europe, with some anti-immigration parties increasing their share of the popular vote, some seeing it shrink, and others remaining very similar to where they were, which could be at a high (e.g. Poland and Hungary) or a relatively low level of popularity (Czech Republic).

The significance of these vote shares is different for every country and depends on national contexts and how other parties are faring. Local politics and political systems are critical to the relevance of election gains. For example, in Belgium the two parties with nationalist (and separatist) platforms have an impressive 28-percent share of the national vote, but other parties have combined strategically to isolate and neutralise them, excluding them from their ruling coalition. Meanwhile, the Sweden Democrats, who won just under 18 percent of the national vote in 2018, have an increasing influence in politics today as potential kingmakers should the opposition, of which they are part, win the next elections. In Italy, the avidly anti-immigration Lega Nord rose rapidly from just four percent in 2013 to around 17 percent in 2018 and is now in a phase of decline. But in Italy’s mercurial politics, opposition to migration remains a strong force with the sudden rise of a new anti-migrant party (Brothers of Italy), which may support Lega’s leader Matteo Salvini in his presidential bid in 2023, or alternatively, eclipse him and go for power alone.

Proportional representation (PR) is the electoral system prevalent in Europe: 40 out of 43 European countries use some form of PR. The UK, with its first-past-the-post system, offers a clear example of where a non-PR model disfavours the far right, which occupies none of the 650 seats in the House of Commons. However, as discussed below, elements of the manifestos of the far-right are increasingly found in the policies of mainstream parties, not least because UK voters chose to leave the EU in 2016, with immigration reportedly an issue of “surging public concern” in the years before the Brexit referendum.

Although it would be rash to draw too many swift conclusions from Table 1, it is clear that right-wing nationalist parties enjoy a high degree of support and power across Europe. Some, like Fidesz in Hungary, and Law & Justice in Poland (as leaders of the United Right alliance), appear unassailable in their dominance of their home political scene. In Switzerland, the Swiss People’s Party co-governs the country and is the largest party in the Federal Assembly having won around 25 percent of the vote in 2018, although some of its support has recently shifted to the Greens. Meanwhile in Estonia, Slovenia, Spain, and to some extent Sweden, rapid gains have been made in recent years by nationalist parties. In Spain, for example, Vox has risen from virtually no votes in 2015 to 15 percent in 2019, and is now the third-strongest party in Spanish politics. Some polls suggest its popularity continues to grow along with the rapidly rising centre-right (populist) Popular Party in the current pro-right-wing, nativist swing away from socialism in Spain.

Conversely, some nationalist anti-immigration parties, many of which used the “refugee/migrant crisis” of 2015 to mobilise support from anxious constituents, have seen their popularity shrink in recent years. Table 1 shows clear declines of some of the more bullish and charismatic nationalist parties which had strong aspirations to lead some few years ago. Examples include Austria’s Freedom Party, the Netherlands’ Party for Freedom, France’s National Rally (known as the Front until a 2018 “de-demonising” re-brand) and the Danish People’s Party. Some of the decline is relatively limited and could reverse, and few are as dramatic as Austria’s Freedom Party, which lost half its support between 2015 and 2019. The case of Denmark is more hybrid and remarkable: the Danish People’s Party’s (DPP) popular anti-migration policies were adopted by the winning leftist Social Democrats while its support fell from 21 percent in 2015 to around nine percent in 2019. As discussed below, the Social Democrats have eclipsed the DPP in their new anti-immigrant, anti-refugee policies and proposals.

The European Parliament consists of 705 elected members (MEPs) drawn from the 27 member states of the EU and organised—uniquely for supranational legislatures—into eight ideological groups.[3] The newest of these, formed in June 2019 by nationalist, right-wing populist and Eurosceptic parties from ten EU states, is the Identity and Democracy Group (ID), which currently holds 71 seats, 10% of the assembly. The centre-right European People’s Party Group (EPP), comprising Christian democrats and conservatives, currently has the highest number (178, just over 25%) of MEPs, while, in second place, the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats (S&D) have 146 (20.7%) seats. The most recent elections for the European Parliament, held in 2019, ostensibly delivered only modest gains to the far right, but, as discussed below, ID’s anti-immigration policies are also espoused by other political tendencies within the assembly.

Beyond Europe

Evidence of nationalistic agendas in combination with anti-immigration attitudes characterising the global political landscape is not hard to find. The trend towards increased authoritarian leadership in global politics has been widely discussed, often accompanied by illiberal, anti-migration nationalistic positions. In recent years, powerful nations like the US, Russia, and China, and emerging states such as India, Brazil, and South Africa have all taken hard-line positions in relation to migrants and refugees to differing degrees. For much of the 20th century, Australia had a “White Australia” agenda. Although this has given way to a more open and inclusive society, with some of the highest global numbers of regular migrants and refugees, Australia’s “stop the boats” policy (more formally known as Operation Sovereign Borders, launched in 2013), a key component of its intolerance of irregular migration, continues to be severe and inflexible. It is arguably in breach of international agreements, but remains popular and supported by parties across the political spectrum. Israel too, appears to have an ever-hardening hostile approach to irregular migrants and asylum seekers.

An exhaustive overview of individual national cases is beyond the scope of this essay, but some highlights illustrate the point:

- Under the Donald Trump administration, the United States became highly exclusionary. It aggressively securitised borders, used trade muscle to force neighbours to comply with its aim of halting irregular migration, issued executive orders to halt movement into the US from selected countries, massively reduced refugee resettlement, and deported millions of undocumented migrants while increasingly practicing apprehension and detention including family separation. Since coming to power in early 2021, President Joe Biden has vowed to end or reverse many of Trump’s policies, but civil rights and refugee rights groups are disappointed at the limited level of reform. Biden’s government has continued to turn away migrants at the border with questionable justification, expelling undocumented migrants and asylum seekers and continues to tell migrants and refugees, “Don’t come”, illustrating how bi-partisan and mainstreamed harsher immigration rules have become.

- Russia’s authoritarian and nationalistic leadership does not welcome refugees or undocumented migrants although the latter have been a central part of the labour supply for years. For the first 15 years of this century Russia hosted very small numbers of refugees. These rose dramatically in 2015 and 2016 during the Syrian refugee crisis and then declined again every year to previous levels. In April 2021, more than a million undocumented migrants from former Soviet states were ordered to leave Russia by June 15 or face expulsion. Racism and xenophobia are commonly reported and anti-Semitism has been a longstanding social reality. President Vladimir Putin’s position on regular migrants has been ambivalent, due to the need to attract millions of workers to support the economy while also supporting a “Russians first” approach.

- In January 2020, India, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), brought into force the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), providing a pathway to Indian citizenship for Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian immigrants from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Bangladesh who had arrived in India before 2015, but the measure excluded Muslims. Critics expressed concerns that the law would be used, along with the National Register of Citizens (NRC), to render a significant number of India’s 182 million Muslim citizens stateless. Widely dubbed as an anti-Muslim law and a “weapon of mass polarisation” it sparked huge demonstrations inside India and condemnation outside. Reportedly anti-immigrant fervour has been fuelled by the political fallout of the act.

- Anti-Muslim nationalism is also seen in China’s widely condemned mass persecution and detention of minorities in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. China’s immigration approach is characterised by strict enforcement of rules against irregular overstays, (including by offering financial rewards to those who inform on migrants), non-hosting of refugees, and deportation of asylum seekers fleeing North Korea, whom the authorities classify as irregular migrants.

- Brazil and South Africa, both famously inclusive and open to migrants and especially refugees, have changed policies in recent years with tougher immigration laws and restricted space for new asylum seekers. Anti-immigration rhetoric and public intolerance of foreigners have revealed themselves in lethal street violence in South Africa and political support for right-wing anti-immigrant leadership in Brazil.

These examples offer glimpses of a wider trend involving many more countries around the world. Are they a reflection of the rise of populism and nationalism or of quasi-authoritarian strongmen undermining democracy and liberal principles? “Almost 70% of countries covered by The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index recorded a decline in their overall score in 2020.” The global average score fell to its lowest level since the index began in 2006.

Immigration has always been a contentious, politicised, and polemical issue. Living in the “age of migration” implies that migration will continue to be prominent in political agendas. To what extent are the politics an expression of the cyclical re-emphasis on migration in response to migration cycles operating through time, displaying periods of contraction and expansion? As suggested by one migration expert interviewed for this Review the world may be witnessing the end of a long period of openness to migration and refugees that started after WW2.

Mainstreaming anti-migration policies

The countries with at least eight percent of voter support for far-right and nationalist parties in Europe listed in Table 1 make up half of all the countries in the region of Europe (including Russia). Other states do not necessarily have popular far-right parties but many well have mainstream parties with significant exclusionary agendas built into their objectives and manifestos.

Considering the prevalence of populism and anti-migrant rhetoric in Europe in 2017, one commentator suggested the real test for Europe was how mainstream parties would respond. So how did they? Recognising the changing tide of public opinion in Europe in the face of the “migrant/refugee crisis” of 2015 and capitalising on the political opportunity of meeting constituents’ demands for more migration management while urgently wanting to head off renewed support for far-right parties, many mainstream parties have adopted more robust and exclusionary migration agendas in the last few years. The rationale for centre-right, centre or even social democrat parties adopting such positions is one of political survival. The effect has been, in some cases, to steal the thunder of the far right and augment support for previously flagging centrist parties.

In Germany, for example, the strength of Alternative for Germany’s fast rise between 2013 and 2019 may be tempered by the fact that most mainstream parties frame their migration policies in a more restrictive and less inclusive manner than they did before 2015. The same is happening in France, the Netherlands, the UK, Denmark, and elsewhere. In 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron was clear that adopting a stricter stance on immigration was designed to lure voters away from the far-right National Rally. His bet paid off and continues to pay off in 2021, when the National Rally fared dismally in regional elections. The level to which centrist parties in the Netherlands have used nativist and anti-immigrant anti-Muslim agenda borrowed from the far-right Party for Freedom is remarkable. Meanwhile, in Denmark, the leftist Social Democrats (SD) swept to victory in 2019 with an immigration agenda adopted wholesale from the Danish People’s Party, an explicitly anti-immigration party with high popularity in 2015 but whose support is fast diminishing. With new laws, the SD are taking the nativist and nationalist agenda to new heights with planned refugee returns, an externalisation of asylum processing, and preventing any further resettlement of refugees and “non-westerners”. It has been argued that the Social Democrats in Denmark are surpassing far-right aspirations.

The mainstreaming of nativist and anti-immigration agendas into more centrist parties’ political manifestos is not the only manifestation of this changing political landscape. Increasingly, traditionally mainstream parties are embracing far-right parties as strategic partners in national and regional elections. In Austria’s 2017 general election, for example, the centre-right Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) ran on a new robustly anti-immigrant platform. This helped ÖVP increase its electoral success and, after the polls, it formed a coalition government with the far-right Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ). In state elections, the right-wing nationalist and populist Alternative for Germany has worked closely with centre- right Christian Democratic Union politicians—the first time in Germany’s post-war history that a mainstream party has relied on the support of the far right to form a regional government.[4] In Sweden, the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats are busy making deals with opposition parties that may give them the role of kingmaker in the coming election; naturally their support will come with a price tag.[5]

Hidden in plain sight

Beyond the precarious twists and turns of state, national, and regional politics that receive significant media attention, there is a sense of something steadier quietly taking shape. Hidden in plain sight, longer-term systemic instruments and policies backed by multi-annual budgets are evolving and enlarging irrespective of the rise and fall of right-wing parties. Examples in Europe include the externalisation of the EU’s borders, the baked-in conditionality of EU development assistance— such as the €79.5 billion Global Europe fund— and the exponential rise in funding for Frontex and other border security entities.[6]

These developments in Europe are echoed in the United States, which is also externalising its borders, not only into Central America but all over the world. The US has a sizable machine that runs large-scale border apprehension, detention, and deportation and is also militarising its border security.[7] The advancement and establishment of these systems occur in relative isolation from national-level politics and are therefore less subject to democratic (voter) scrutiny or accountability. In the US they function irrespective of who is in the White House or which party dominates Congress, and in Europe have occurred at a time when the far right only occupies 10 percent of the European Parliament’s seats and governs none of the 27 EU countries.

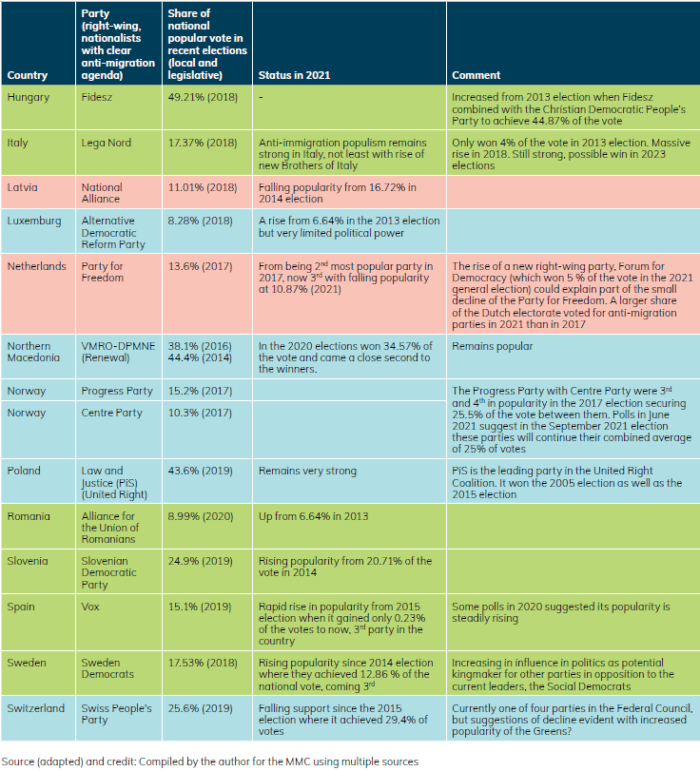

Anxiety over irregular migration is not confined to Europe and the US. In 2019, a UN survey found that in all regions of the world except Northern Africa and Western Asia most governments regarded the number of irregular migrants on their soil to be a matter of “major concern” (see Figure 1). It is hard to determine whether policy or government-level positions are reflected in public attitudes. Gallup, Ipsos, WorldValuesSurvey, and the Pew Research Centre all measure public opinion on migration issues, but their methodologies and specific survey questions vary widely, as do their conclusions, with some showing swings towards more welcoming attitudes towards migrants and others the opposite. In this author’s opinion, drawing conclusions about the hardening or softening of attitudes towards migration globally from such polls is hazardous and open to bias.

Whether the general public (the voters) are increasingly negative towards migration and politicians merely responding to those sentiments by adopting anti-migration narratives and policies therefore remains something of an open question. It could be, as some polls indicate, that the general public on average is not so negative, but that the dynamics between the media— and social media in particular—a very vocal minority, and populist politicians distort reality and create a misleading picture of increasingly negative public attitudes towards migration, possibly creating self-fulfilling conditions. Moreover, it should not be ruled out that some populist politicians actively drum up negative public attitudes towards migration for political gain.

Normalising the extreme

There has also been a clear ratcheting up of what this and previous editions of the Mixed Migration Review calls the “normalising the extreme”. Across the world, and especially in Europe and the US, many actions, some illegal, are taken against migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers that until recently would have been considered beyond the pale, inhumane, or unethical (and still are by many), but which are now common yet face minimal scrutiny or impactful condemnation.[8]

Appetites for refugee burden sharing

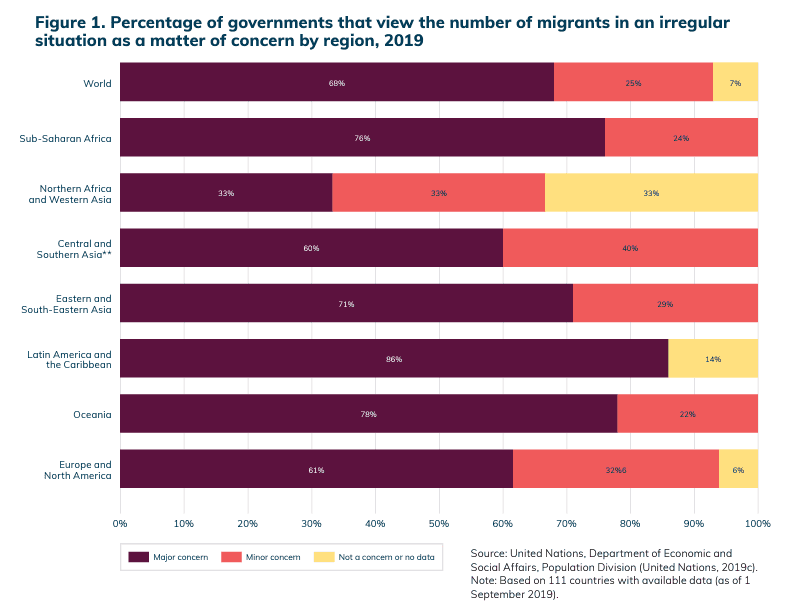

The global appetite to receive and host refugees registered by UNHCR in resettlement programmes has always fallen far short of demand, with figures in 2020 being the lowest ever (see graphic below). But while a paltry 35,000 of the world’s 20.7 million refugees were resettled in 2020, a far greater number of people made successful claims for asylum. EU states for example, issued 521,000 first instance decisions on asylum applications that year, leading 211,800 people being granted some type of protected status, including refugee status. Almost 70,000 others won asylum in appeal or review rulings. For asylum-seekers who arrive in the EU irregularly therefore, there is a good chance of being granted refugee status or other kind of permission to stay, providing an incentive for irregular movement, something the EU and its member states are determined to curtail. The UK’s moves to change asylum laws to penalise asylum seekers who arrive at its shores irregularly in boats across the English Channel—strongly criticized by UNHCR—also illustrate this resolve.

As at 28 February 2021. Only the top 11 countries of resettlement are included. Resettlement includes here only those resettled with the involve- ment of UNHCR. Source: Refugee Council of Australia 2021 (page 5)

More generally, willingness to “share the refugee burden” globally is unimpressive and countries are prepared to expend considerable resources to deter irregular migration and thereby reduce the number of unignorable asylum seekers in their own countries, many of whom will eventually find a way to be accepted according to domestic law.

Migrants and asylum seekers are routinely pushed back and pulled back on land and sea, shot at, sound-blasted, deported, roughly handled, and aggressively denied access or the chance to apply for asylum by countries that have ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention. Some commentators are asking how relevant the convention is now, in a context where respect for the norms on which the refugee regime is based appear to be in “serious decline”. In a recent interview, UNHCR’s assistant high commissioner for protection said that protection standards have “deteriorated significantly in the three years since the Global Compact on Refugees was established”, but that part of the reason was the impact of Covid-19.

‘Covidisation’ caveats

2020 and 2021 have been extraordinary years due to the many impacts of the coronavirus pandemic. Its effect on migration movement, migration governance, and migration politics continues to be documented.

The sense of wartime solidarity in many countries has led to increased support for incumbent leaders and their parties, particularly when vaccine rollouts started to give constituents hope. Meanwhile, support for anti-migrant parties seemed unreasonable when so many of the “front-line” workers in OECD countries were either regular or irregular migrants. Has Covid-19 slowed the advance of anti-migrant parties as people realise the importance of migrant workers, or conversely, has it made people more fearful of outsiders? Many governments used the pandemic as a pretext to implement harsher immigration controls and surveillance measures. The extent to which current attitudes and events will continue after the pandemic is subdued—and how this will in the longer run influence the support for hard-line anti-immigration parties—is still uncertain.[9]

Conclusion

With or without those parties that rose to prominence and secured votes on anti-migrant platforms in the recent past, their policies and values remain prevalent in migration politics in Europe and elsewhere, such as in the US, Australia, ASEAN countries, Russia, and India. Should we be shocked when left-leaning social democratic parties adopt harsher immigration policies, or is this the acceptable cost of keeping the far right out of mainstream national politics? Should political leaders be so responsive to popular perceptions, or instead dare to take unpopular decisions that they feel are morally correct—as Angela Merkel did in Germany in 2015 when she opened the doors to Syrian refugees—despite the antagonism and political backlash she unleashed?

Shocks like the coronavirus may serve to exacerbate a more conservative and protectionist approach to immigration and increase hostility or reduce openness to foreigners. Despite some positive developments in various countries—such as releasing people from immigration detention, increasing access to citizenship, providing Covid vaccines and other health services to undocumented migrants, and the large-scale regularisation of undocumented migrants[10]—the environment is currently looking bleak for international mixed migration, and anti-migrant approaches are increasingly normalised in mainstream parties and institutionalised in border and development policy.

Is this just a cycle, or a taste of things to come, as various interviewees in this Review predict? By associating the rise and fall of populism and nationalism with attitudes to immigration and asylum, some miss the point that while populism may have passed a high-water mark (for the moment), the evidence for new trends and the mainstreaming of a widespread anti-migrant policy environment is strong. Indeed, far from being just paper tigers that are in decline, there is salient evidence of their abiding influence.

[1] This essay is framed as a follow-up to “The Politics of Mixed Migration”, an essay published in the 2019 edition of the Mixed Migration Review.

[2] Broadly, anti-migration agendas are commonly explicit in nationalistic, often far-right parties which may be ‘populist’ and, if European, often also Eurosceptic.

[3] Groupings within the handful of the world’s other multi-country assemblies are based on nationality rather than political ideology.

[4] Raj, K. (2020) op. cit.

[5] Duxbury, C. (2021) op. cit.

[6] See the essay on Lucrative Borders by Mark Akkerman

[7] See the interview with Todd Miller on page 229

[8] See Normalising the Extreme, Page 200

[9] See the essay by Alan Gamlen and Bram Frouws – Post-pandemic paradigms: Covid-19 and the future of human migration on page 232

[10] Explored further in ‘Normalising the Extreme’ on page 200.