In late 2018, the Italian government began implementing a new legislation that restricts access to protection for refugees and migrants in the country and hardens border security to deter incoming irregular migration. The “Salvini decree” is the first major legislative act by Interior Minister Matteo Salvini, leader of the populist League party that won 17 percent of the votes in the March 2018 election after campaigning on an anti-migration agenda.

A main goal of the new law is to send home hundreds of thousands of undocumented migrants. But this goal is impossible to achieve because Italy lacks readmission agreements with most countries of origin of the migrants it wants to send home. At the same time, the Italian agriculture sector’s growing reliance on undocumented foreign workers incentivizes migrants to come or stay in Italy, exposes them to dangers, and hinders the country’s economy.

What’s in the Salvini decree and whom does it affect?

The main provision of the new Italian legislation is the abolishment of humanitarian protection, a form of temporary protection issued to asylum applicants who did not qualify for refugee status or for subsidiary protection, but were recognised as vulnerable. Instead of humanitarian protection status, the Salvini decree introduces “special permits” for specific foreigners who prove to be victims of a limited set of circumstances or have serious health issues.

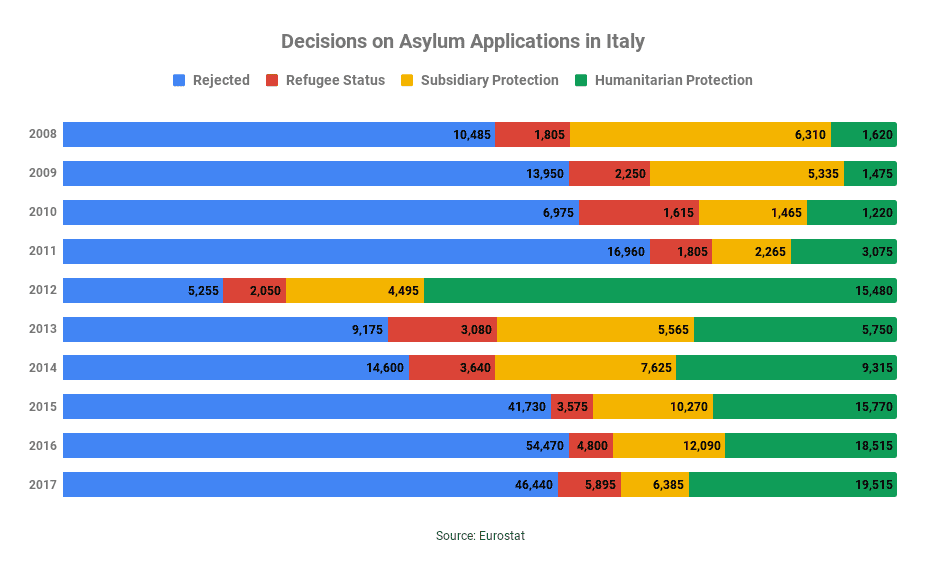

Abolishing humanitarian protection is significant because in the past few years it had been the most common form of protection in Italy; it was granted to about 100,000 asylum seekers since 2008, including a quarter of all applicants in 2017. Those who had been granted this status received a 2-year, renewable residence permit and the right to work. According to the Salvini decree, people who had been granted humanitarian protection status will be re-evaluated once their residence permits expire.

Another group that will be affected by the “Salvini decree” are people whose asylum request is pending; there are currently about 107,500 pending asylum applications in Italy. The decree stipulates that social services such as Italian language courses, vocational training and legal assistance will be withheld until the end of the asylum process, except if the applicant is an unaccompanied minor, which will hamper integration prospects for those allowed to stay. The decree also stipulates that people whose asylum process is being examined cannot obtain an identification document, which in Italy is a precondition for signing an employment contract, renting a house, opening a bank account, accessing public housing, enrolling to public health care, and applying for welfare subsidies. Furthermore, the decree extends from three to six months the period of time Italian authorities can detain new arrivals while their identities and nationalities are being verified, and allows for the revocation of protection status for those convicted of certain crimes.

The 19th of February, the Italian Cassation Court established that the Salvini decree is not retroactively applicable before October 5, 2018, when the new law went into effect. It is unclear how the new ruling will be received and implemented by the regional asylum commissions, but it is likely that the impact of the new restrictive measures over the ending cases will be somewhat lessened by this new ruling, as most of the protection requests that are currently being processed were made prior to the issuing of the new law. However, the restrictive measures will still apply to new arrivals and, more importantly, to those who will have to renew their permits, estimated at approximately 40.000 people over the next two years, whose humanitarian permits will now not be extended.

Un-deportable, and in demand

In the medium/long term, the decree will cause thousands of asylum seekers and people with temporary protection status to lose their residency permit but there is no mechanism to get them to leave Italy. Many cannot be returned to their homelands because Italy does not have readmissions agreements with most of the relevant countries in Africa. Between 2013 and 2017 Italy managed to repatriate only 20 percent of all rejected asylum applicants, and in the second half of 2018 returns were 20 percent lower than during the same period of 2017.

Salvini’s intention is for those who aren’t granted any type of protection to be detained at repatriation centres, but there is not enough room in these centres for all the people who are supposed to be repatriated. The number of operating repatriation centres decreased between 2013 and 2017, and even though new centres were developed last year, the overall detention capacity is still much lower than what is required.

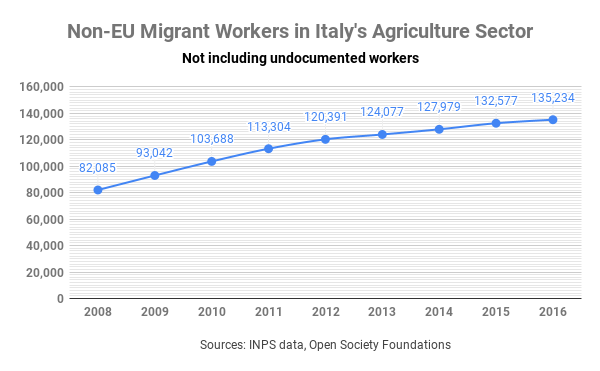

Another major obstacle to Salvini’s plan is the constant and growing demand for foreign workers in Italy’s agricultural sector. Farmers in Italy, who are economically squeezed by an oligopolistic food industry, have increasingly transitioned from local family labour to foreign workers because the latter are often paid considerably less than the legal minimum wage. As of 2015 roughly 48 percent of the agricultural workforce (about 405,000 people) were not Italian.

About 344,000 of these foreigners were employed without a contract, according to a 2018 study by the European Policy Institute. Most of them live in degrading and unsanitary conditions, and frequently face exploitative working conditions, including having their identity documents confiscated by mafia-like middlemen called ‘caporali’ and being subjected to severe abuse and forced labour.

Number of undocumented migrants rising (again)

Italy’s inability to send home most rejected asylum seekers on one hand and its increasing demand for migrant workers on the other have caused the number of foreigners living undocumented in the country to increase since 2013. As of January last year there were 533,000 undocumented migrants in Italy according to official estimates; these people are not registered with any government offices and live on the margins of society without legal right to work or access to social services.

According to Matteo Villa, a researcher of the Italian Institute for International Political Studies, the “Salvini decree” will cause the number of undocumented migrants in Italy to spike even more. Villa calculated that about 70,000 people[1] are at risk of becoming irregulars in Italy by end-2020 due to the elimination of humanitarian protection – leading the number of foreigners living irregularly in Italy to climb to 670,000. In his post about the “Salvini decree” Villa pointed out that such high numbers of undocumented people is not a new phenomenon in Italy, and that previous Italian governments responded to increases of undocumented people with mass regularizations: in 2002-2003, about 700,000 migrants were regularized; in 2006, about 350,000 undocumented were regularized; and in 2009 another 300,000.

Regularisation and legal entry channels

One of the recommendations of Alessandra Corrado, author of the European Policy Institute study, is for Italy to create permanent regularisation mechanisms, whereby migrants who can demonstrate that they have lived in the country for a number of years and are employed, are able to gain legal status. John Dalhuisen and Gerald Knaus, from the European Stabilisation Initiative (ESI), argued that to address the increase of undocumented migrants, Italy needs to have a more effective entry system for foreign workers to meet labour demand in sectors such as agriculture. They suggest that Italy offer African countries an annual contingent of regular visas in return for their cooperation on readmission agreements.

But both regularization of the undocumented and the creation of legal pathways for economically driven migrants are highly unlikely considering the securitised migration agenda of the current Italian government. Meanwhile, the impact of the “Salvini decree” is starting to be felt. In January, more than 500 people were ousted from a refugee reception centre in a town close to Rome, and Salvini announced his intent to shut down Italy’s largest reception centre – which houses 1300 people – within a year.

The “Salvini Decree” claims to better control migration and to make Italy more secure. In practice, considering Italy’s lack of readmission agreements and the lack of provision to regulate employment of foreign workers, it is going to increase the stock of irregular migrants in the country. Moreover, it is reducing the protection space for refugees and migrants, hampering integration for those who will be allowed to stay and pushing even more people into vulnerable situations. In sum, the analysis shows that the decree will likely cause more problems than it solves. It is therefore highly doubtful that it will lead to better governance of mixed migration in Italy.

[1] Following the ruling of the Italian Cassation Court, the elimination of the humanitarian protection will not apply to pending cases and therefore this number should go down to 40.000 individuals (see graph 1 here)