The following article was originally compiled for the Quarterly Mixed Migration Update, Europe, Quarter 1, 2024 and has been updated and reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

Since November 2023, Finland has undertaken the closure of its borders with Russia in response to rising irregular arrivals, from a few dozen to hundreds within months. This measure initially deemed temporary until mid-April, has ignited a broader legislative push within Finland. Proposals not only seek to prolong border closures but also aim to toughen immigration and asylum regulations, despite vocal opposition from international bodies and human rights groups.

Finland asserts that Russian authorities are orchestrating the influx of asylum seekers and migrants towards the Finnish border, alleging facilitation of travel and accommodation, culminating in border crossings often via bicycles or scooters. The bilateral tensions between Finland and Russia have escalated significantly since Finland’s alignment with NATO and the EU following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The timing of these events, coinciding with the rise of right-wing sentiments and anti-immigrant rhetoric in Finnish politics, underscores the complexity of the situation. What transpires at the Russo-Finnish border extends beyond a mere security response; it is emblematic of broader shifts in European migration policy towards measures that weaken the right to asylum and enhance border surveillance and enforcement.

This article examines the situation at the Russo-Finnish border, laying out the timeline of events and looking into the related shifts in border management and approach to asylum in Finland. It argues that these developments, while situated in the specific context of the souring relationship between Russia and Finland, also reflect broader trends in European migration management and human rights discourse.

Finland claims Russians funnel asylum seekers through borders

Finish authorities accuse Russia of recently funneling asylum seekers and migrants towards the Finish border, facilitating their travel, accommodation and final ride on bicycles or scooters across the border zone before they all apply for asylum on arrival in Finland. In September 2023, thirteen people sought asylum in Finland after crossing the Russian border. In October, that number rose to thirty-two, and in the first two weeks of November, it was 500. According to the government, approximately 1,300 asylum seekers arrived in Finland via the eastern border in November, December and January. They say it is clear that foreign authorities have been facilitating instrumentalised migration which, if escalated, risks posing a serious ‘threat to national security and public order’ in Finland. Normally, people without valid visas are prevented by Russia’s FSB Border Guard Service to enter the Russian border zone. In late 2023 and early 2024 the border guards let migrants through the checkpoints without the travel documents, often selling or giving them bikes to travel the last 5 km and thereby bypass the rule banning people from walking between the Russian and Finnish border checkpoints.

No laughing matter

The relatively low number of predominantly Syrian and Somali asylum seekers riding children’s bicycles through the snow to reach the Finish border may conjure a somewhat humorous if not farcical image, but for Finland it is no laughing matter. They see these events as a form of “hybrid warfare” in reprisal for Finland’s security cooperation with the US and NATO, which it joined, despite Russian disapproval, in April 2023. Finland recognises that its eastern borders are not only the outer limits of the EU Schengen area but a new front line between NATO and Russia along their shared 1,340 km border.

An end to pragmatic cooperation

Previously Finland was neutral in its position towards Russian foreign policy, but after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine it aligned itself to NATO and the EU positions – heralding an end to its longstanding pragmatic cooperation with Russia and a distinct chilling of relations. Since joining NATO, Finland has stepped up military training of reserve units and border surveillance, allowing NATO planes to patrol the border airspace – also angering Russia. In response Putin stated he was reestablishing the Leningrad Military District – an administrative move he said could lead to a buildup of troops in the regions east of Finland. Russia now sees Finland as a hostile state as part of the ‘Western coalition’ and presumably Finland will respond accordingly.

Russia’s instrumentalising of irregular migrants and asylum seekers at Finland’s borders may be a form of testing Finish reactions while also enjoying seeing the sociopolitical policy panic and the frequent shift to right wing populist politics caused in Europe by irregular migration.

A threat already anticipated

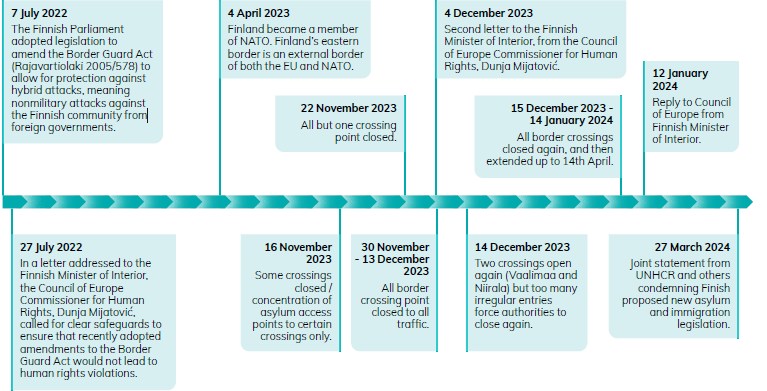

Interestingly, Finland had already anticipated cross border non-militarised actions of this kind two years earlier. Specifically, following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and actions by Belarus, the Finnish government’s own security review noted the risk of Russia or Belarus directing asylum applicants en mass towards the Finnish border to ‘destabilize’ the country. On July 7, 2022, the Finnish Parliament adopted legislation to amend the Border Guard Act (Rajavartiolaki 2005/578) to allow for protection against nonmilitary, so-called hybrid attacks from foreign governments – including temporary border closure. Shortly afterwards in a letter addressed to the Finnish Minister of Interior, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović, called for clear safeguards to ensure that recently adopted amendments to the Border Guard Act would not lead to human rights violations.

Bilateral tension of this nature – as a result of using migrants ‘against’ a neighbouring country as a form of weaponised migration diplomacy had been seen, inter alia, in Belarusian anger with the EU (at their Polish, Lithuanian and Latvian borders); from Turkey against the EU (at their Greek border and in Cyprus) and in Moroccan disagreements with Spain. At the end of November 2023, Estonia threatened to copy Finland in response to Russia – and by February 2024 both Estonia and Russia had closed vehicle passage between their two countries.

A gift to Finland’s anti-migrant, anti-refugee lobby

In mid-2023 a new right-of-centre government took over in Finland in a coalition government which includes the far-right Finns Party. Immediately after taking power, the new government with the far right politicians heading the interior ministry, announced plans to crack down on immigration in what they called a necessary ‘paradigm shift’ – this included aiming to halve the number of refugees the Nordic country receives through the UN refugee agency from 1,050 a year to 500. In 2021, around 8.5 percent of Finland’s population, or 470,000 people, were of foreign origin.

In this context, Russia’s action with asylum seekers and migrants may have been a gift to the anti-migrant agenda of the new government and the Finns Party. With the Finns party now the second largest in Parliament and a reported 80 per cent of surveyed Fins approving of the current border closures there is a strong tailwind for lawmakers to push through a tough new Bill on asylum regulations. The Proposal which is being pushed through Finish parliament rapidly will include legislative amendments designed to help ‘strengthen border security and effectively combat any attempts to put pressure on Finland in the form of instrumentalised migration’. Apart from allowing for continued border closures, it aims to half the number of asylum seekers Finland takes annually, reduce refugee’s benefits, make citizenship harder, reduce family reunification and increase deportations of those not accepted for asylum. According to UNHCR, if activated, asylum-seekers, albeit with some exceptions, would be prevented from accessing Finnish territory, removed from the country, and redirected to a different entry point where applications for international protection would be accepted. More contentiously, it allows border guards to make decisions concerning access to Finish territory for further processing while the new laws would also enable faster asylum processing with a view to returns back to Russia for those rejected – assuming Russia would cooperate by accepting them.

For the law to be adopted, a five-sixths majority vote in Parliament is required. Additionally, a consultation period has taken place until March 25th, after which the law is meant to be swiftly adopted. On 15th March, the Ministry of the Interior sent out for comments the draft act (on temporary measures to combat instrumentalised migration). The proposed act is scheduled to enter into force as soon as possible but would be temporary and would be valid for one year after its entry into force. It does appear the government may be effectively using the ‘crisis’ to push through a raft of measures that in another context may have met more scrutiny and resistance.

Rights groups and UN’s fear and condemnation

However, Finland’s movement towards harsher refugee legislation and the closed border crisis has not escaped scrutiny or resistance from the UN or rights groups, even if the laws have similarities with the EU’s newly passed Pact on Migration and Asylum. In early December, Dunja Mijatović, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, wrote to the Minister of Interior of Finland, Mari Rantanen, strongly condemning border closures and requesting assurance and clarifications concerning the planned Bill. The Minister responded on the 12th January with a unapologetic defence and justification of Finland’s actions: ‘It is the state’s job to effectively protect its borders and territory. If we continue to be naïve, unreservedly open, we will lose the support of the people’.

Seeing things develop in an alarming manner, on the 27th March, UNHCR went public boldly with an announcement insisting that Finland should not violate international agreements by restricting the rights of people in need of protection. This was a joint statement from UNHCR Nordic and Baltic Countries, the Finnish Red Cross, the Finnish Refugee Council, and the UN Association of Finland, directed to the Finish government. They claimed Finland is in the process of introducing a new bill that would ‘instrumentalize asylum seekers and refugees to achieve political goals’ through the restriction of access to various border points in their long eastern land border with Russia. Furthermore, the UNHCR statement claims that the Finnish proposal conflicts with international and European refugee and human rights law, and reminds Finland that pushbacks are illegal and ‘the principle of non-refoulement is a non-derogable obligation under international law that applies to all states and cannot be deviated from’. UNHCR has also produced a detailed legal analysis of the proposed bill explaining its deficiencies and contraventions of international law. To date no pushbacks have been perpetrated but according to international law, closed borders that deny asylum seekers ability of apply for asylum at an international border is also in breach of the principle of non-refoulement.

It appears that external condemnation and fear in relation to forthcoming legislation has had little impact on Finish legislators, but it still needs to pass a high bar of positive votes in parliament before it becomes law.

Summary timeline related to the current situation:

Call for increased military involvement in migration control

In the midst of these developments, Finland and Italy are pushing for expanded military involvement in migration control, as outlined in a “non-paper” presented to the EU Foreign Affairs Council in late April. The non-paper, outlines measures aimed at “countering the instrumentalization of migration and migrant smuggling”, advocating for increased cooperation between the EU and NATO. It suggests leveraging tools such as the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy missions to provide strategic advisory and capacity-building support in partner countries. Additionally, among other measures, it highlights the importance of forging comprehensive partnerships with key countries of origin and transit, citing the EU’s Memorandum of Understanding with Tunisia as a potential model. There is no mention of the adverse effects that these proposed responses to the instrumentalization of migration can have on the rights and wellbeing of migrants.

… and shrinking asylum space

What may look like a temporary border security response, by Finland, to an increase in, but still very low number of asylum seekers from Russia is more likely to be part of a longer-term action that responds to shifting attitudes in Finland towards asylum seekers and a serious and longer-term chilling of bilateral relations between Russia and Finland. Meanwhile, the asylum space shrinks again in trends that are sweeping Europe and are likely to be echoed in multiple EU countries during the forthcoming national and EU elections in 2024, not to mention already captured in the new EU Pact on Migration and Asylum which rights groups have already condemned.