The following essay was originally compiled for the Mixed Migration Review 2023 and has been reproduced here for wider access through this website’s readership.

The essay’s author Dr Samuel Okunade is a Senior Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Pretoria. Dr. Okunade holds a doctorate degree in Conflict Transformation and Peace Studies.

Introduction

According to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), “Free movement of people across Africa represents a powerful boost to economic growth and skills development when people can travel with ease for business, tourism or education. Everyone benefits from a country that opens up their borders as well as the country whose nation is on the move, as seen in the growth in remittances in recent years.”

In 2018, when the African Union Assembly adopted both the Protocol to the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community Relating to the Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment (AU Free Movement Protocol) and the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), UNECA’s director of regional integration declared that “continental integration is an existential necessity, and therefore a natural destiny for Africa.”

African leaders have been talking about continentwide free movement for decades. The concept featured prominently in the Lagos Plan of Action for Economic Development of Africa 1980-2000 and was codified in the 1991 treaty that established the African Economic Community (AEC) and again in the 2018 protocol, and is a key pillar of the AU Agenda 2063. But although (as this essay will detail) progress has been made at the individual state and regional level, it is a destiny that still seems to lie some way over the horizon. More than five years after the AU Free Movement Protocol was signed by 33 African states, only four—Rwanda, Niger, Mali and São Tomé and Príncipe—have ratified the instrument, well short of the 15 required for it to enter into force.

There is wide consensus that intra-African trade is being stifled by entry rules that prevent citizens moving from one country to another and that “freer movement would lower transaction costs, increase trade and make production more efficient.” According to UNECA, “Trade experts, business executives and advocates of the AfCFTA from across the continent have repeatedly expressed concerns about the slow progress on the ratification” of the AU Free Movement Protocol.

Broader implementation of the AU Free Movement Protocol would enable African countries to tap into a wider labour market to bridge skills gaps while trading across borders, mirroring the EU Schengen Agreement (originally signed in 1985), which eventually created a single external border and abolished the internal borders between 27 EU member states. But in Africa, the widely recognised benefits of free movement appear to be outweighed by a range of concerns that have deterred—or at least de-prioritised—wider ratification of the AU Free Movement Protocol. These include civil and international conflicts and insurgency; rising criminal activity; unequal economic growth; border porosity; rapid urbanisation; a youth-heavy demographic rise; and the overarching and urgent implications of climate change.

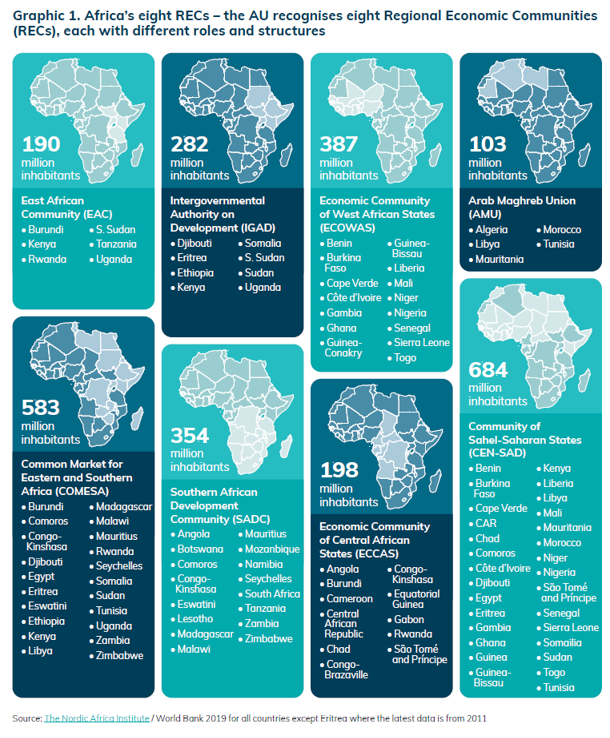

This is not to say free movement is at a complete standstill in Africa: progress is being made, but at a regional rather than continental level. The African Union recognises and has formal relations with eight regional economic communities (RECs), overlapping groupings of African states that developed independently to boost economic integration between their respective member states. All RECs have already introduced their own free movement protocols, and although these have not all been formally implemented in full, several of their key provisions are already in effect. This essay will chart some of the dynamics and processes that characterise a selection of regional and continental agreements related to integration and assess how close Africa is to its “natural destiny” of free movement.

Free movement models in Africa

At the sub-continental level, several agreements are already in place that facilitate free movement to varying degrees. While all eight RECs have adopted free movement protocols, an overview of three is sufficient to explore progress to date as well as the challenges facing this key aspect of continental integration.

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Protocol on free movement

ECOWAS was established in 1975 with a core mandate to remove obstacles to the free movement of persons, goods and capital so as to enhance economic development in West Africa. In 1979 ECOWAS adopted the pioneering ECOWAS Protocol on free movement of persons, goods and capital, which aims to deliver a borderless West Africa.

The ECOWAS protocol stipulates the rights of entry, residence and establishment of businesses that were supposed to have been rolled out in three phases over 15 years. Although the third phase (relating to the right of establishment) has yet to be implemented, the protocol has already enhanced free mobility and delivered economic and trading benefits across the ECOWAS region, not least through the introduction by member states of a 90-day visa-free window. However, this freedom is not absolute: anecdotal evidence suggests that when they lack correct documentation (and even sometimes when they have it) border corruption, harassment and red tape lead some ECOWAS citizens to cross borders irregularly and sometimes to use smugglers.

The ECOWAS protocol is a landmark agreement whose full implementation has been impeded by political and security concerns, economic factors, and a weak legal base.

East African Community (EAC) Protocol for a common market and the free movement of persons

In 2009, the heads of state of the East African Community (EAC) signed a protocol to establish a common market and free movement of people, which went into full force in July 2010. This protocol aims to accelerate economic growth and development by enabling the free movement of goods, capital, services, persons and labour, and to put in place the right of establishment and residence.

The EAC protocol has led to the introduction of an East African passport and temporary passes to facilitate free movement of EAC citizens between member states. Special immigration lanes have been created for easy passage of EAC citizens through the various airports in the sub-region. But like its ECOWAS counterpart, full implementation of this protocol has been stymied by various factors, such as political barriers, trade tariffs, high transportation costs and discrepancies in standards, among others. Similarly, corruption, harassment and human trafficking act as barriers to comprehensive free movement, not least that of migrants and refugees.

The Southern African Development Community’s (SADC) Protocol on the facilitation of the movement of persons

The 2005 SADC protocol on the facilitation of the movement of persons aims to progressively remove all barriers to the movement of persons, goods, capital, and services amongst the bloc’s 16 member states in line with the objectives of the SADC Treaty. After some member states—notably Botswana, Namibia and South Africa— rejected an initial draft prepared in 1997, the protocol text was revised to reduce the extent of, or remove some, rights. Consequently, unlike the ECOWAS and EAC agreements, the SADC protocol does not give SADC citizens the right to reside and establish businesses in other member states. But even this revised text faces opposition, with South Africa, for example, resisting the adoption of Phase 1 of the protocol—relating to the right of entry and the abolition of visas for nationals of other SADC states—until certain conditions are met.

However, although the protocol has yet to come into force for lack of sufficient ratifications, some member states have struck bilateral and multilateral agreements to facilitate a degree of mutual free movement of their citizens, including by (in line with the protocol) permitting visa-free entry for up to 90 days. Around 80 percent of SADC citizens can now travel visa-free or are granted a 90-day visa on arrival in another SADC country. But when it comes to longer-term migration in the region, more conditions apply that require documentary evidence. Coupled with administrative delays and costs, this leads some migrants to travel irregularly, particularly from the low-income member states to wealthier ones, such as South Africa.

Continental drift

Pan-Africanism is the overarching agenda of the African Union, which aims to increase cooperation and integration of African states to drive the continent’s growth and economic development. While Pan-Africanism may have been a powerful unifying sociocultural and political ideology for African states prior to and during the anti-colonialist and anti-apartheid era, it has struggled to deliver economic and structural integration.

AU established the AfCFTA with the aim of facilitating free trade through the creation of a single African market. All but one (Eritrea) of the AU’s 55 member states signed the agreement in 2020 and, by January 2023, 44 had ratified it. Although such a high consensus around this trade agreement might suggest a renewed appetite for a borderless Africa, very few countries on the continent have committed themselves to free movement at a continental scale. Moreover, trading activities to date under the AfCFTA have been minimal as only eight countries—Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania and Tunisia—are participating in the agreement’s Guided Trade Initiative.

As meticulously detailed by the Africa Regional Integration Index (a project led by the AU Commission, UNECA and the African Development Bank that ranks African states by various aspects of integration), freedom of movement varies enormously across the continent.28 This component of the integration index scores countries (on a scale of zero to one) according to the number of other countries whose nationals require a visa or who can obtain one on arrival, and on whether they have ratified the AU Protocol. A dozen countries, including Libya, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Burundi, and Algeria (which all require visas from most other African citizens and none of which have signed the AU Protocol) have scores of around 0.1 or less, well below the continental average of 0.441.

The prevalence of low free movement scores on the index highlights the bureaucratic challenges faced by individuals travelling within Africa. These hamper their ability to engage in business activities and tourism and to contribute to the broader integration of the continent.

Three countries scored a perfect one on free movement: Comoros, Djibouti, and Somalia, which citizens of no other African countries require visas to visit, and which adhere to the AU Protocol. The wide disparity between African countries’ free movement scores on the integration index clearly demonstrates that there is a long way to go before the dream of a borderless continent becomes a reality.

Challenges to implementation

There are various endogenous and exogenous factors responsible for the non-implementation and full operation of the AU Free Movement Protocol. These include the state-centric mindset and lack of political will by many African leaders; political and security concerns; overlapping interests vis-à-vis the RECs; scapegoating of migrants for political and electoral gains; and the externalisation of European borders into Africa.

State-centric mindsets and lack of political will on the part of African leaders

Many African leaders and governments hold state-centric views which may be reflected in their approach to migration issues. Thus, migration is viewed as a threat and not as an opportunity. Sensitive to their electorate’s concerns about large numbers of immigrants competing in what are already regarded as scarce job and opportunity markets, politicians are often wary of open borders. Equally, they fear the political implications of any dampening of already low wages with increased supply of cheap(er) workers. These concerns are especially prevalent in Africa’s upper middle-income countries. Despite ample evidence that increased migration results in economic growth, the considerable economic disparity across the continent gives pause, particularly among the more successful economic magnets such as Nigeria, South Africa, Ghana and Kenya. All African states belong to one or more of the continent’s RECs, which have their own structures to facilitate free movement between member states, but the fact that they are not fully implemented points not only to technical obstacles but also to reluctance at the political level.

Far from opening them up, many African countries have been securitising their borders to prevent entry by undocumented or unauthorised migrants from neighbouring countries and beyond. This also impedes free movement of their own citizens in the process. Such border management may include the establishment of multiple checkpoints with heavily armed security personnel, as found in ECOWAS member states, especially Nigeria. Similarly, in the SADC sub-region, member states have made movement along their borders difficult. South Africa, for example, has fortified its border with fences, walls and mobile patrols. However, it should be noted that border porosity is also widespread, and for those that wish to, crossing most African borders irregularly is not difficult, especially when assisted by smugglers.

Political and security concerns

Such porosity allows non-state actors such as rebel groups and insurgents to move across borders and indeed entire regions with ease, at a time when there are more than 35 armed conflicts taking place in Africa. Non-state actors with a multi-country presence include terrorist groups such as Boko Haram in the west and centre of the continent and al-Shabaab in the Horn and the east. Governments thus remain wary of any move aimed at removing or opening up their borders, while analysts warn of the security risks of a “borderless Africa”.

The proliferation and movement of rebel groups in countries such as Chad, the Central African Republic, Sudan and Uganda across porous borders have facilitated the proliferation of small arms and light weapons across the continent. And the movement of combatants and weapons from Libya into Mali and the Lake Chad region strengthened the Tuaregs and Boko Haram respectively, escalating the conflict in the region colossally. Porous borders and governments’ inability to secure them have aggravated the spread of insurgency, violent extremism and terrorism in sub-regions and the continent at large.

Arguably, porous borders and poor border management have also facilitated the proliferation of other cross-border criminalities such as human trafficking, as well as arms and narcotics smuggling. Since 2019, Africa—especially West and Central Africa—has become a significantly more important transit zone for Europe-bound cocaine. Meanwhile, Southern Africa ranks high in relation to the trafficking of women and children. These examples touch on reasons why African governments are less inclined to open their borders than to securitise them in order to prevent incursion and/or movement.

The AU Free Movement Protocol has been held back primarily by the security concerns and socio-economic imbalances that exist on the continent. Another, related, factor is the absence in many African countries of efficient systems of registration and identity document production. Some member states such as those in SADC and others have stated various concerns must be addressed before the protocol can be fully implemented.

In the sub-regions where free movement arrangements are already in place, such as in the ECOWAS and EAC zones, such movement has been facilitated by new forms of common documentation. For example, the ECOWAS Travel Certificate or the ECOWAS Biometric Passport is used across the ECOWAS zone for entry stamps at the start of the permitted 90-day stay. In a move to further simplify and automate movement across borders, ECOWAS has introduced the ECOWAS National Biometric Identity Card, which Nigeria and Senegal took the lead in introducing in 2016. These cards carry travellers’ biodata (which are also stored in a central database) and can be used at automated gates at various points of entry within the sub-region. To date, however, only six ECOWAS member states currently support these cards. In addition, extensive harassment, intimidation, and extortion have been reported at roadblocks and checkpoints (both official and illegal) along borders in West and East Africa. This impedes not only the free movement of individual travellers, but also, by extension, the implementation of regional free movement agreements.

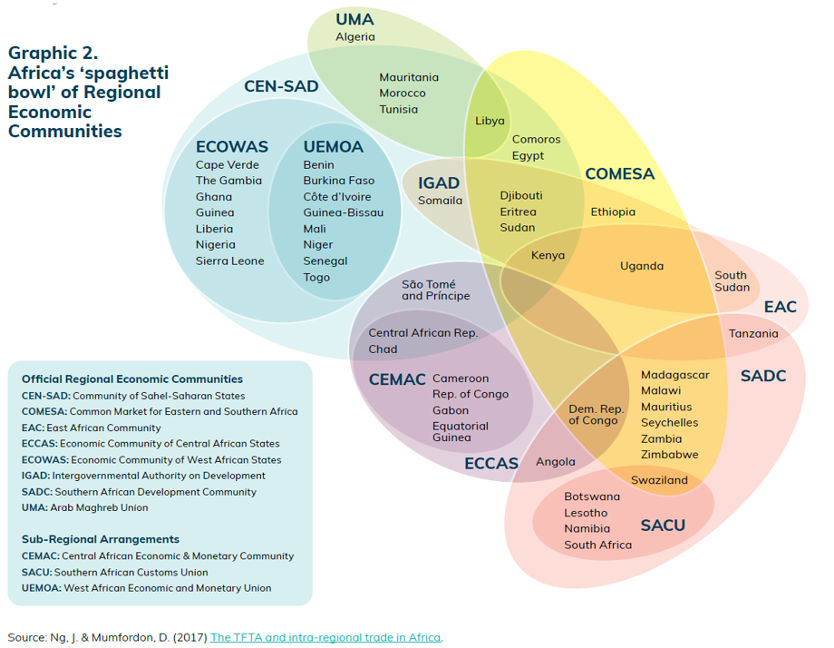

The RECs ‘spaghetti bowl’

As noted above, Africa’s RECs have a broadly shared ambition of facilitating regional economic integration between their respective member states and are seen as the building blocks of continental unity. However, their proliferation and overlapping memberships have spawned a “spaghetti bowl” of agreements (see Graphic 2 below) characterised by varying degrees of policy confusion, misalignment, duplication and fragmentation on a range of issues, including free movement. Some see the RECs spaghetti bowl as a recipe for rivalry and wasted resources. Belonging to multiple RECs with different policies inevitably offers states the chance not to implement some agreements or to defend their activities by citing alternative commitments. By definition, RECs deal more directly than continental initiatives with regional issues that affect their member states. RECs also entail a degree of regional accountability, while continentwide agreements are harder to police or enforce. Still, given that some RECs have already advanced their own free movement arrangements, one might have expected more members of such blocs to embrace the AU Protocol. But, as previously mentioned, only four African countries have ratified this crucial instrument.

Scapegoating migrants and instrumentalising xenophobia

Migration remains a highly polemical subject with incendiary political implications in most countries globally. Regardless of the strength of their evidence base, several factors, including security concerns, economic fears and underlying xenophobia, appear to influence most societies’ perception of immigration and thus contribute to a widespread resistance to open borders. And despite some positive examples of multinational integration elsewhere in the world—such as the EU or the Southern Common Market (Mercosur)—such resistance is profound in Africa, where it seems to be exacerbated by the continent’s diverse cultures, beliefs and languages.

At difficult times, such as in economic recession or flagging political support, African leaders tend to blame their countries’ woes on other African migrants and mobilise anti-foreigner sentiment. Similarly, citizens can be quick to accept this as tenable reason and, as such, take to the streets to rally against migrants and refugees. This often culminates in the expulsion of migrants, and in extreme instances, in xenophobic or “Afrophobic” violence which has been manifest in various African states, particularly South Africa.

For example, in 1969, Ghana expelled many African migrants. Nigeria did the same between 1983 and mid-1985 while Côte d’Ivoire followed suit in 1999. In the SADC sub-region, especially in South Africa, African migrants have been blamed for the economic downturn, limited access to health care, criminalities and job losses for locals. In 2015, a nationwide spike in xenophobic attacks against immigrants in South Africa prompted a number of foreign governments to begin repatriating their citizens. One analysis suggested at least 350 foreigners were killed between 2008 and 2015. Inter alia, attacks are typically against migrants from Zimbabwe, Mozambique, DRC and Somalia. Often truck drivers, shop owners and other entrepreneurs are targeted and incidents occur every year up to the present.

Some 62 percent of respondents to a survey conducted in South Africa in 2018 said they viewed immigrants as a burden on society by taking jobs and social benefits, while 61 percent thought that immigrants were more responsible for crime than other groups. Some South African political parties have also made anti-migrant plans and programmes the core of their manifestoes, while government officials have been known to make inciting statements against migrants. In June 2021, a xenophobic vigilante group called Operation Dudula was set up with the aim of forcing out undocumented migrants. The group has been seen visiting schools and hospitals calling for the exclusion of foreigners. In September 2023 the group registered to become a political party ahead of next year’s general elections, with a plan to campaign on a platform for expelling foreigners. There have also been public debates featuring complaints about foreigners holding key positions in government.

In February 2023, widely publicised racist and xenophobic comments by the president of Tunisia led to a wave of violence against Black Africans across the country involving both civilian mobs running amok and police officers who detained and deported dozens of people. Meanwhile, Kenya for some years has threatened to repatriate hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees, many of whom have lived their entire lives in in Kenya, after declaring them, with little evidence, to be a security threat. People of Somali origin in Kenya are regularly subjected to discrimination and harassment.

Externalisation of European borders into Africa

African countries are variously points of departure and transit for mixed migration to Europe, and in some cases both. The European Union has positioned itself as a partner with Africa on border and migration issues. Previously, the EU actively supported the free movement agenda in Africa although this changed after the European “migration crisis” of 2015/16. The EU began negotiating and conditionalising its development aid on Africa’s cooperation in the field of migration control and consequently free movement regimes were increasingly sidelined within the EU’s migration policy framework and programming. Despite this, there are also parallel examples of European support for African free movement. The EU has recently been focused on tackling the “root causes” of irregular migration and enhancing economic development in Africa as a way to curb migration—especially irregular migration—towards Europe. Its Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) is a key manifestation of this focus. As one analyst put it, the EU’s “irregular migration agenda is crowding out funding for longer-term, regionally owned, migration priorities.” Nevertheless, the EU continues to support free movement initiatives in certain regions, such as ECOWAS and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (made of eight member states in the Horn of Africa), albeit with an understanding that this should not translate to wider free movement towards Europe.

To control inward migration, the EU has also deployed various measures such as fortifying its borders through the establishment of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (better known as Frontex), and through various funding channels and financing mechanisms (such as the aforementioned EUTF).

The EU increased its influence on Africa’s migration agenda through its dealings with North African countries such as Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Libya as well as states in West Africa. It has deployed militarised defensive strategies, such as naval and air assets, dispatched technical and security experts to West African states and erected a digital border control infrastructure at the Rosso border crossing, which has impeded free movement between Mali, Senegal and Mauritania. It has also turned Niger, previously a major transit country, into its “immigration officer” thus impeding free movement along certain routes across the ECOWAS region. The case is somewhat different in the IGAD region as the EU, through its trust fund, has supported the bloc’s free movement protocol while at the same time striving to reduce migration towards Europe.

Any attempt by Black African migrants to cross into the Maghreb region is met with resistance as they are perceived to be on their way to Europe. Furthermore, this movement provides a lucrative illicit economy of smuggling and modern slavery for criminals and militias in the region, with much-documented egregious human rights violations against migrants and refugees. Arguably, the EU has successfully incentivised poorer neighbours to do the “dirty work” of preventing migration into Europe and turning a blind eye to the accompanying rights violations.

In short, the EU’s efforts to shore up and externalise its borders to prevent irregular migration have helped delay the roll-out of free movement of people in Africa at both the regional and continental levels. But despite their purported focus on “root causes”, such efforts risk being counterproductive: if lack of free movement stifles development on the continent, those who are determined to find better opportunities outside their own country will now be more, not less, likely to seek them out in Europe rather than other African states. Various EU efforts to secure their own bloc from irregular migrants, therefore, has threatened the implementation process of free movement arrangements existing across various sub-regions in Africa. Let alone across the entire continent from south to north as this would technically mean African migrants and refugees could travel across multiple borders uninterrupted until they reach Africa’s Mediterranean coast as the last stop towards Europe’s external borders. The EU could be said to have taken a gamble on externalising its borders and using migration diplomacy and ‘conditionality’ of development assistance by privileging the restriction of movement above more open borders on the continent.

Concluding reflections

According to the IOM, migration cannot be disentangled from development and the “free movement-development nexus” should not be overlooked. Migration facilitates the supply of labour (both skilled and unskilled) and in the process boosts development and strengthens economic relations between countries. This is the reason for the establishment of common markets, as well as the facilitation of free movement of persons, capital and services. Europe set a good example with the EU, and that is why Africa is trying to mirror what Europe did through its RECs and, more recently on a continental basis, through the AU Free Movement Protocol and the AfCFTA.

There are some concerns about a potential influx of people from low-income countries to middle-income countries in Africa, which could strain their resources and infrastructure – there are, and were, similar concerns within Europe. However, others argue that states would benefit greatly if free movement continued on the continent. Not only could this reduce unemployment, but it could also increase efficiency in the job market and decrease the need to import skilled workers from outside of Africa. Furthermore, with broader freedom of movement, African investors will have more opportunities to explore new markets, establish businesses, and create employment in the region, which will lead to an increase in intra-African investment. Implementing the AU Free Movement Protocol alongside AfCFTA is key to fulfilling the goals of the AU Agenda 2063. Ultimately, with free movement and trade expected to contribute to longer-term sustainable economic development, this could even reduce irregular migration from Africa to Europe in the long run.

Despite the arguments in support of free movement, African governments are currently dealing with urgent issues that prevent the swift implementation of this approach. The continent is already facing both sudden and gradual environmental challenges such as climate change that lead to resource stresses and population mobility. These factors add to the main obstacles outlined in this essay. If large numbers of people were forced to move because of climate change in the coming decades, the question of open borders may become irrelevant as people will simply vote with their feet regardless of regulations and official immigration policies. Although a borderless Africa may seem like an appealing and logical future for a more unified continent, it is an unfeasible objective unless some pressing issues are addressed.