The Mixed Migration Centre held a side event on the 15th of November at COP27 on the value and use of knowledge on climate mobility for response. Supported by the Global Centre for Climate Mobility and the Robert Bosch Stiftung, as well as the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, the panel comprised Priscilla Achakpa, Founder and Executive Director of the Women Environmental Programme; Ritu Bharadwaj, Lead on the Governance of Risk, Climate Change Group, International Institute of Environment and Development; Raphaela Schweiger, Migration Programme Director at the Robert Bosch Stiftung; and Jane Linekar, Head of Research & 4Mi, Mixed Migration Centre.

Stories of Climate Mobility: Key Findings from the Mixed Migration Centre

After an introduction to MMC, its work on mixed migration, and its 4Mi primary data collection programme with refugees and migrants travelling in mixed migration routes, MMC presented some key findings from its research on climate mobility so far. These findings come from a number of stand-alone studies, 4Mi data, and MMC’s field research for the African Shifts report for the Africa Climate Mobility Initiative.

Download the presentation file here

Understanding the links between climate change impacts and mobility: a framework

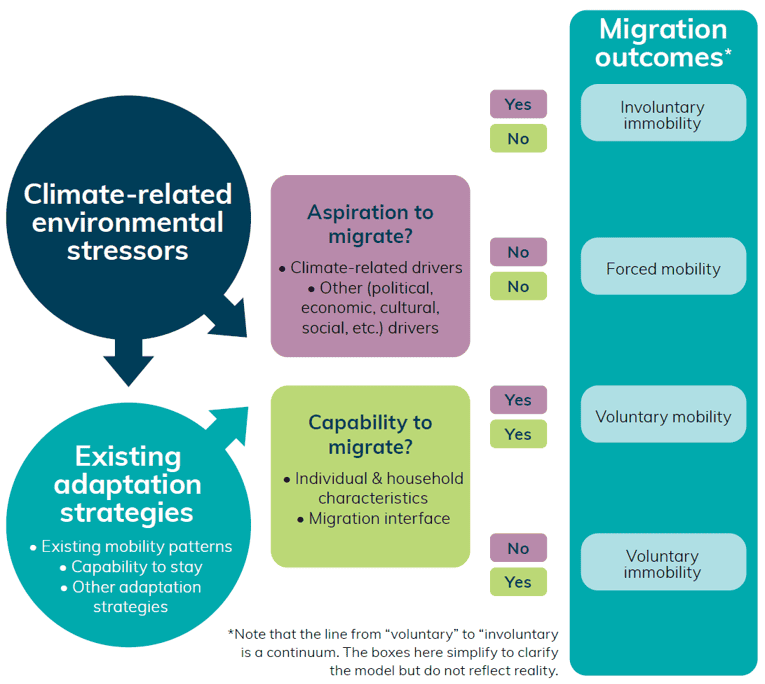

The mixed migration lens is very well suited to exploring climate mobility, as it takes an inclusive approach, looking at all the drivers of movement, and encompassing multiple mobility outcomes.

MMC has developed a framework to better understand how environmental and climate-related factors play a role in mobility. By applying this framework, we can find out about people’s capability (and aspiration) to adapt to the impacts of climate change, including their capability and aspiration to move. And we can find out what this means in terms of mobility outcomes. Voluntary migration and forced displacement are, of course, not binary conditions but represent two ends on a continuum, but for simplicity, we determine four main mobility outcomes.

Being able to more accurately answer questions about the impact of climate factors on the aspiration and capability to move allows for a better-informed discussion around resilience and adaptation, and to develop policies that will meet the needs of populations impacted by climate change. This framework can be used not only as a research tool, to gain a better understanding of the relationship between climate change impacts and mobility, but also in practice, to work through solutions to challenges relating to climate impacts and mobility.

The indirect nature of climate-related drivers

MMC’s 4Mi data shows how refugees and migrants think about climate and environmental factors in relation to their decision to move. Analysis of approximately 20,000 interviews held in 2021 and 2022 with people who had left countries in Asia, West/Central and East Africa, and Latin America, shows that most people embarked on the migration journey for more than one reason. Environmental factors are rarely reported (1-5% of respondents). Economic drivers are the most common, reported alongside conflict and insecurity, or lack of rights and freedoms, or lack of access to services and corruption.

However, when we ask specifically whether environmental factors played a role in the decision to move, between 20% and 40% say yes. This reflects the indirect role of environmental factors, as illustrated in our framework. Environmental factors weigh on the decision to migrate through their effects on safety, and on economic wellbeing.

This provides useful knowledge for global-level thinking and decision-making, but it is only when we look more closely at particular groups that we find the knowledge to inform targeted responses. Climate mobility is different for different communities, population groups, and individuals. Four ‘stories’ from MMC’s research have been selected here.

Women in Karamoja: vulnerability among an immobile population

In the agro-pastoralist community we visited in Karamoja, Uganda, women were more frequently engaged in agriculture, yet they did not and could not own property or land. They were affected by environmental impacts but unable to make decisions to address them.

Climate events were impacting on women’s lives alongside other dynamics. 75% had experienced several episodes of drought or dryness in the past decade, but Two-thirds also mentioned land degradation, which is the result of a combination of factors, not just climate change. Insecurity was a concern. Most women were pessimistic about future environmental impacts, yet the vast majority – 82% – were not considering moving. There was instead an optimism about personal circumstances, and finding ways to cope and adapt. However, the strategies reported do not appear sustainable. Women’s hands seemed to be tied.

Beira: a wish and need to move, but not far

The city of Beira, Mozambique, was devastated by Cyclone Idai. It is repeatedly hit by storms and tropical cyclones, and also faces sea-level rise. Climate-related events are impacting on health, safety, and livelihoods. Here, our research found that moving was considered normal, most people wanted to move, and 40% felt forced to. Displacement is a norm: women and children move more frequently than men, as men tend to stay behind to maintain their livelihoods. But people did not want to move far – most prefer to stay in the city.

Bangladesh and Honduras: the climate is contributing to the decision to move

We found that, while environmental factors are not a primary driver for most respondents from Asia, a third of Bangladeshi migrants we interviewed reported them. Many of these migrants had resorted to smugglers to leave Bangladesh. They face risky journeys as well as insecurity or exploitation after reaching their destination: while they do not feel they can live well at home, many do not find safety at the end of their journey.

A similar story came from Hondurans we interviewed, heading towards North America. 19% of Honduran migrants and refugees that we interviewed considered environmental factors a direct driver of movement, behind economic conditions and violence. Almost half of them thought it threatened their survival.

Most of the people we spoke to were travelling with children on the treacherous routes to North America, convinced that they could no longer stay in Honduras. Again, people are resorting to highly dangerous journeys because they see no alternative.

Key messages: on drivers, and on outcomes

- The link between climate change and mobility is complex. To understand how we get from climate change impacts to a mobility outcome we have to take numerous factors into account. Climate impacts strongly affect livelihoods, but also health, security and other factors. Ultimately, climate impacts can often be characterised as a stress multiplier: adding to the challenges people are already facing, and increasing motivations to move, or obstacles to movement.

- It’s important to underline the lack of movement. Immobility – whether related to will or capacity – is more of the norm than perhaps current narratives suggest. Generally, when thinking about adaptation and coping, people are thinking about how to stay. Mobility is not generally perceived as a positive or sustainable adaptation strategy.

- Mobility, such as it is, is primarily internal. The distances are short. Cross-border movement is rare, although it is happening. Stories of large-scale transcontinental migration provoked by climate change are unlikely. Rather, the movement we see will amplify the urbanisation trend, and in particular, will grow secondary cities.

Linking knowledge to action on climate mobility

Knowledge can prevent oversimplification, but also tease out the complexities, and clarify how we can act. With knowledge we understand that mobility can be both positive and negative, but so can immobility, which can be both a sign of positive adaptation in place or signal that people have run out of all coping mechanisms and don’t have the capacity to move We can use knowledge to understand how to achieve sustainable adaptation, how to enable people to stay, and how to move. Through this understanding, we can take concrete measures that will work.

Panel discussion

Without evidence, policy makers will not take civil society and other advocates seriously. At the same time, bringing knowledge to policy makers assists their understanding and brings nuance to their decision-making. As an example, to understand the dynamics of the Boko Haram crisis and violence in northern Nigeria: without the knowledge brought by experts, some policy-makers do not appreciate that the crisis can only be fully understood – and effectively addressed – by considering the impacts of the shrinking of Lake Chad.

Local expertise is vital, especially for understanding women’s conditions, and how global events and dynamics impact on individuals’ livelihoods. Taking a bottom-up approach means learning and gaining knowledge from local people, including what they need and want. At the same time, people who want to assist affected populations have their own expertise, and can and should bring information too.

A lot of research exists on concepts and landscapes around climate impacts and mobility, but there is less on people’s realities of climate mobility. Findings from communities show that climate change impacts are not felt in isolation from other dynamics; and where climate and environmental factors do play a role in movement, people who are engaged in forced displacement and distress migration come from the more vulnerable populations affected by disasters. Across all settings, physical and mental health and wellbeing are important and underreported climate impacts, whether people stay or move.

But it is hard to use case studies with policy makers. They need numbers. IIED found that people displaced by slow-onset disasters are far more likely to be trafficked than those displaced by sudden-onset disasters. This is because of a lack of early warning systems for slow-onset disasters. A lack of investment in disaster risk reduction means not only that more people are displaced, but that they are exposed to greater risks when displaced.

Conversations with policy makers relating to knowledge and data reveal some specific gaps: “I have disaster risk reduction money and don’t know how to spend it”; “there are so many reports I don’t have time to read them”; “I have no resources to generate the data I need”. It seems we are making progress on producing knowledge, and on policy makers demanding evidence, but we need to move further forward on bridging gaps on getting the right knowledge and resources to the right people in the right way.

Questions from the floor considered how to bring together the various communities engaged in producing and using knowledge, and how to turn that knowledge into targeted messaging and demands to COP27 negotiators. The same question was asked of donors – financing for climate mobility is clearly needed, what are the messages for them? Is there a problem in policy makers’ acceptance of and trust in knowledge and data?

Mobility is not being recognised sufficiently by negotiators or by the people writing the National Adaptation Plans. It is being left out despite being an essential concern, just one of which being how cities are going to deal with the increase in population and informal settlement, which is already happening.

Loss and damage is a key issue for COP27. It may seem obvious that that there is no discussion of loss and damage issues without mentioning mobility issues – since losing homes, livelihoods, lands and health due to climate change can all drive mobility. However, migration expertise and climate expertise are still too far apart, and there is often a lack of capacity to address mobility related to climate change, and understand what knowledge is required.

How to get policy action?

- Knowledge is essential, and policy makers demand it, but data and knowledge generation does not guarantee action. Media attention is vital – lack of action for slow-onset disasters can be attributed to lack of funding, and media attention helps to determine funding decisions.

- Different actors require different types of knowledge. Concrete actions at a local level must include local knowledge, so financing needs to adapt to different communities’ needs and make provision for different groups within that community, women, youth, and minority groups.

- Different constituencies should work together to make clear demands, backed up with data.

This panel brought together a range of: researchers, negotiators, practitioners, and donors; experts in climate change and experts in migration. It made clear the need for knowledge and evidence, and brought home the need to connect and bridge between the different realms of expertise. Climate change and mobility are global issues cutting across policy sectors, and are themselves interconnected. The 2018 Global Compact for Migration refers to climate change, primarily as an adverse driver of migration; at the COP27, mobility was also recognised: the decision regarding to the loss and damage fund cited the challenges of “displacement, relocation, migration” (paragraph 6b). These are first steps, and it seems that recognition is growing, that this bridging is essential to ensure effective action on climate mobility.