The rapid fall of Kabul to the Taliban in mid-August took many by surprise, casting further shadow on the future of a country already at breaking point. Since the beginning of the year, hundreds of thousands of Afghans have been displaced and forced to seek refuge in neighboring provinces, and across borders in nearby countries as political and economic instability has mounted.

However, the full impacts of the current situation on migration and displacement are yet to be seen. While many Afghans who are in search of safety, security and a better future would like to leave the country, unprecedented large-scale movements from Afghanistan are yet to eventuate and many Afghans remain in a situation of involuntary immobility. This is a result of the closure of land borders, increasingly securitized responses from neighboring countries, increased Taliban checkpoints, as well as already limited regular migration pathways, now even less available due to the closure of most consular services in Afghanistan and the challenges of acquiring or renewing passports.

In response to increasingly restricted movements and the changing landscape, the Mixed Migration Centre’s (MMC’s) 4Mi[1] enumerators situated across Afghanistan and in Turkey, have been reporting an increased reliance on smugglers, the formation of new routes, increased costs of journeys and escalating protection risks. To mitigate mounting risks and prevent considerable numbers of Afghans embarking on risky irregular journeys, it is imperative that states in the region and beyond work together to provide safe, regular, and effective pathways for those seeking to leave. This includes states in the region, as well as the EU keeping their borders open to those seeking protection, increasing humanitarian intake quotas, providing swift and effective options for family reunification, as well as accessible labor migration pathways, and providing urgent support to neighboring countries hosting the largest share of displaced Afghans.

Fears of large-scale movements has fueled anti-refugee and anti-migrant rhetoric, as well as increased the securitization of borders

As concerns about the humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan rise, neighboring countries and the EU have adopted drastic and preventive measures in fear of a repeat of the so-called 2015-2016 ‘refugee crisis’. In the days leading up to Taliban takeover, the Iranian government deployed troops along its borders with Afghanistan to not only counter any security threats, but to also prevent the irregular entry of Afghans into the country. Pakistani officials have repeatedly warned that the country does not have capacity to host more Afghans within its territory. Despite the current uncertainty facing Afghanistan, both Iran and Pakistan have deported Afghans crossing irregularly, without visas, into their territory, a continuation of their policy of deporting hundreds of thousands of Afghans in recent years. Iran has also vowed to ‘immediately repatriate refugees’ once conditions improve, and in the first week of September alone, deported 33,893 undocumented Afghans. Other countries in the region, including Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, have also signaled they would push back against any attempts to cross the border without permission.

Meanwhile, Turkey has sped up the construction of a concrete modular wall and smart tower on its eastern border to prevent the irregular crossing of Afghans from Iran. Since August, xenophobic rhetoric has been rising, with hostile posts emerging on social networks targeting Syrian and Afghan asylum seekers. These posts have occurred alongside rising tensions between refugees and host communities in Ankara, with altercations resulting in the death of a Syrian refugee. Simultaneously responses from the Turkish government remain hardline, with the continued arrest and detention of refugees and people seeking asylum across the country.

It’s getting really difficult to get to the Turkey because of the walls and border controls. Crossing the border used to be much easier as many Afghans were able to reach Istanbul. However, these days, a high number are caught and sent back to Iran border… even the behavior of Turkish police is becoming different, they are more violent and reckless.

4Mi enumerator in Istanbul, Turkey, interviewed September 2021

Securitization of borders and pushbacks is also increasingly common in Europe. Along with increasing its sea patrols, Greece has also built a 40-km long wall on its border with Turkey and opened its first refugee holding camp on Samos Island. As a result, only 604 Afghans have arrived in Greece since January this year. Along the Balkan Route, Croatian police were alleged to have robbed and pushed back about 60 Afghan asylum seekers to Bosnia between 16 and 29 August. Poland too has sealed off its 418-km border and unlawfully pushed back Afghans into Belarus, disregarding international refugee law and leaving all in precarious situations with no access to food, clean water, shelter or medicine, which has so far led to the deaths of four people.

Increasing securitization and a lack of regular pathways has led to increased reliance on smugglers, new routes, increased costs, and escalating protection risks

As the already limited regular pathways to leave the country for Afghans have narrowed further, the majority of those who seek to leave in the coming months may have no choice but to consider embarking on irregular journeys with the assistance of smugglers.

Even before the Taliban’s quick accession to power, the number of Afghans trying to enter Iran irregularly had increased dramatically, reaching to 5,000 per day in July. In recent months, thousands of Afghans have arrived in Pakistan as well. In Kandahar, thousands entered Pakistan via the Chaman border crossing during the first week Taliban took control, with reports of many more congregating at the borders since then, seeking to cross irregularly in lieu of other viable options. Smaller numbers of Afghans have also reportedly crossed irregularly into Tajikistan to the country’s north.

Since the beginning of the year, MMC’s 4Mi enumerators based across Afghanistan have been reporting that migrants and refugees have a growing reliance on smugglers as they must navigate increasingly policed and militarized borders, as well as the closure of land crossings and cessation of consular services across the country.

There are many people in Zaranj these days who want to flee from Taliban rule, both families and single individuals. They all want to go to Iran or Pakistan because they are afraid for their lives… There are not enough Qachaghbars [smugglers] or vehicles to take Afghans across the Pakistan border. Hotels are full and many locals are renting their houses to migrants.

4Mi enumerator in Zaranj, Nimruz, interviewed in August 2021

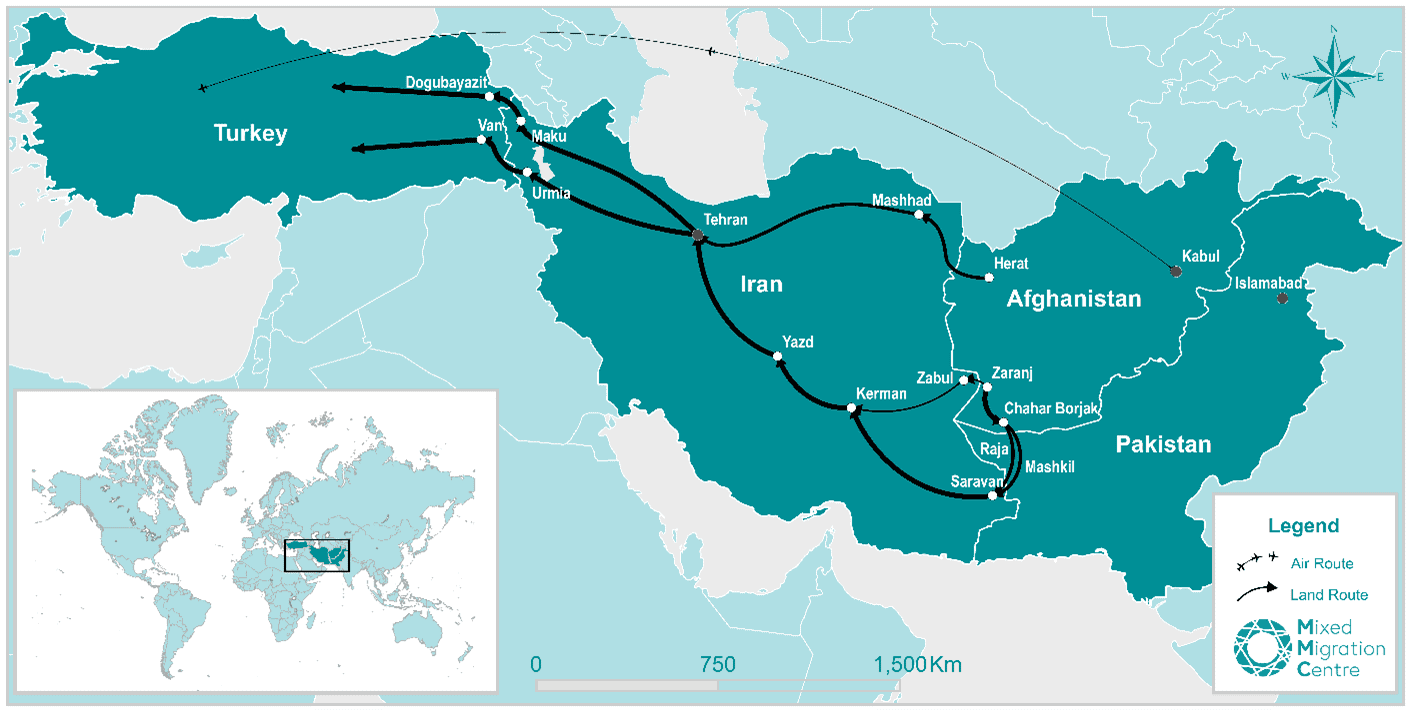

In terms of the routes that smugglers are using, the so called ‘Mashkil’ and ‘Raja’ routes through Pakistan territory have long been the main avenues to reach Iran from Afghanistan (see Map 1 below). However, in recent months MMC’s 4Mi enumerators have reported that some smugglers increasingly use a route via Zabul province to smuggle Afghans into Iran. While the route is shorter, it is much more precarious as people must climb or dig tunnels under walls erected at the border by Iran. Although the chance of getting caught by Iranian border guards is much higher on this route than others, it is increasingly being used by members of the typically Shia Hazara ethnic group, as they seek to avoid increasing presence of extremist groups including ‘Jundallah’ in Pakistan who are targeting the minority due to their religion along the Mashkil and Raja routes.

In the country’s west, 4Mi enumerators in Islam Qala, Herat Province, have also reported that since the Taliban took control of the country, temporary routes have emerged with some Afghans, including families, trying to reach Iran by crossing the border at Herat and Farah provinces. Usual irregular routes to travel to Iran go through Zaranj, however recently, routes to Iran via Herat and Farah provinces have been increasingly chosen as they are cheaper than more traditional routes. These routes come with more risks, including a greater chance of being caught and deported back to Afghanistan by Iranian guards (see Map 1 below).

At the Iran-Turkey border, MMC’s 4Mi enumerators have reported that two routes remain most popular for entering Turkey, the ‘Maku to Degubeyazit’ route and the ‘Urmia to Van’ route. While ‘Urmia to Van’ remains the main route for those who want to reach Turkey via Iran, the ‘Maku to Degubeyazit’ route has been increasing in popularity since the beginning of the year (see Map 1 below).

Map 1. Most prevalent routes taken by 4Mi Afghan respondents to reach Turkey

In terms of the costs of smuggler services, MMC data collection shows a significant increase in the costs of journeys from Afghanistan for different destinations over the past few years, and particularly in recent months. For example, the cost of journeys from Zaranj, Afghanistan, to Tehran, Iran has increased from USD 250 in Q1 2020 to USD 320 in August 2021. Similarly, the cost for a Turkish visa obtained through an intermediary has also increased from USD 2,500 in Q1 2020 to USD 5,500 in July 2021. These increases are in large part due to growing demand for smuggling services considering the deteriorating political and security situation in Afghanistan, as well as increasing pushbacks at the borders, making smuggling operations more complicated and costly as they seek to avoid detection or are required to pay increased bribes to officials.

The smugglers are more afraid of getting caught now because there are many more border guards than before. So many smugglers just show Afghans the way to cross the mountains and how to reach the next village. But without a smuggler to guide them the whole way, many get lost in the mountainous terrain where some die out of hunger and thirst or freeze to death during the cold nights.

4Mi enumerator in Van, Turkey, interviewed October 2021

Table 1. Average smugglers’ fees (USD) charged for three different destinations

| Departure | Destination | 2020 | 2021 | |||||

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | ||

| Zaranj | Tehran, Iran | 250 | 300 | 290 | 270 | 250 | 270 | 320 |

| Zaranj | Istanbul, Turkey

(Land route) |

1500 | 1700 | 1710 | 1900 | 1850 | 2000 | 2200 |

| Kabul | Istanbul, Turkey

(Visa) |

2500 | – | – | – | 2700 | 4000 | 5500 |

| Spin Boldak | Quetta, Pakistan | 85 | 105 | 100 | – | 90 | 95 | 123 |

In terms of protection risks experienced en route, there have been growing reports in the media of pushbacks at the borders of neighboring countries, and further afield in the EU, as a result of increasing securitization. There have also been reports of large crowds gathering at the borders with Pakistan and in some cases stampedes of people trying to flee resulting in tragic fatalities. Reports in neighboring border towns, such as Quetta, Pakistan, have also included increasing extortion of Afghans as opportunists look to take advantage of those in desperate situations.

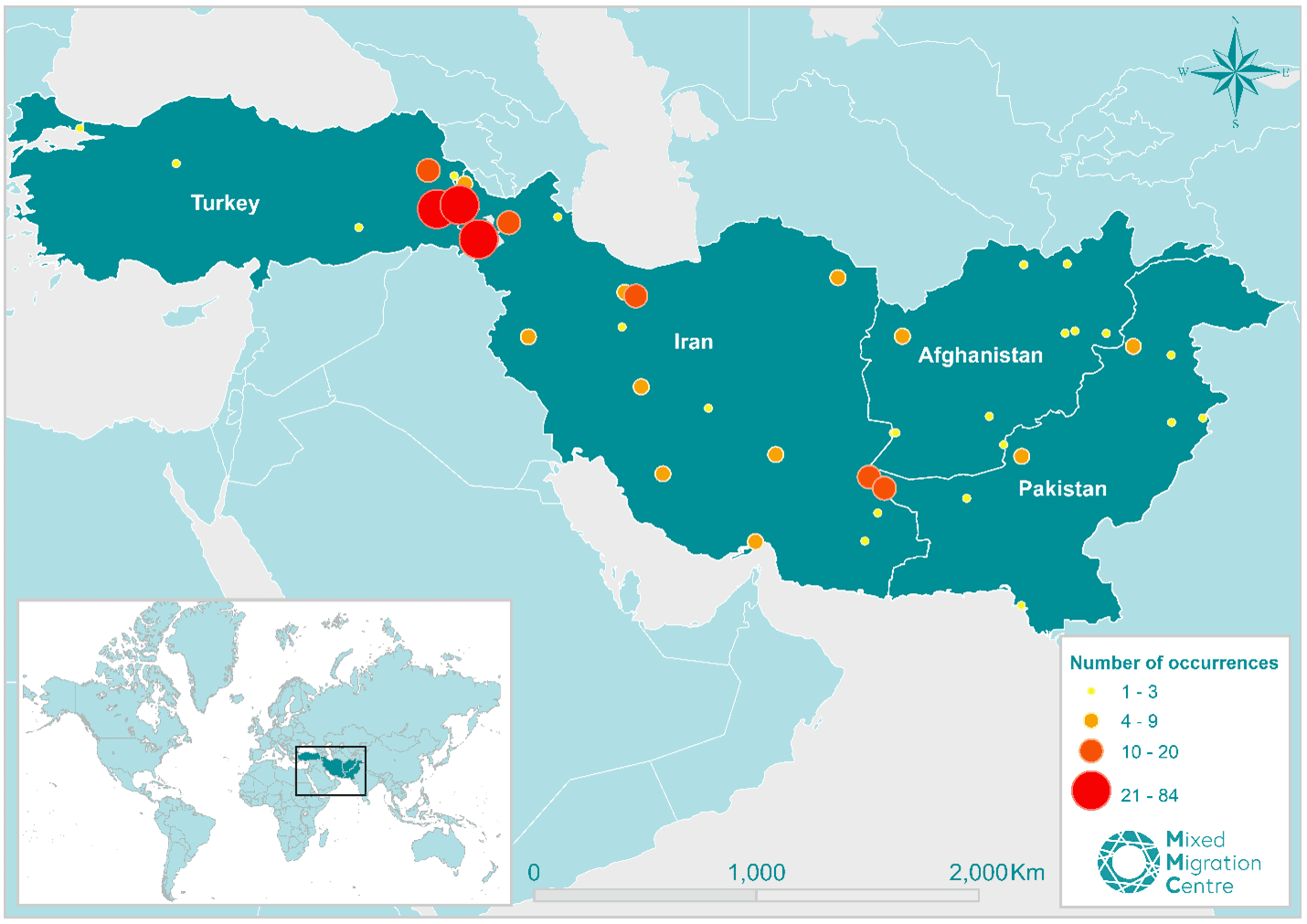

In Turkey, MMC has interviewed 423 Afghans since August 2021. The findings show physical violence, death, robbery, and detention to be the most prevalent types of protection risks along routes from Afghanistan to Turkey via both Pakistan and Iran. Most of the dangerous locations en route reported by 4Mi respondents were within Iran or Turkey (153 out of 211 locations), see Map 2. Those interviewed reported that smugglers (35%), border guards/immigration officials (28%), military/police (27%), and criminal gangs (18%) were the most common perpetrators of protection violations. These findings are in line with recent reports claiming Iranian police have robbed and shot Afghans who were pushed back by Turkey at the border.

Most Afghans we interview experience risks and violence on the way to Turkey. They go through many difficulties, especially women and children. The dangers and risks are not only in one or two places, they are everywhere throughout their journeys. In Iran, there are accidents, there are shootings, arrests, and beatings by police. In Turkey, it’s almost the same, there are arrests, deaths because of the harsh weather, and some Afghans have drowned in the Lake.

4Mi enumerator in Istanbul, Turkey, interviewed September 2021

Map 2. Most dangerous locations on route for Afghans interviewed in Turkey (n=423)

What will the future hold for Afghan displacement and migration?

Although the current situation has not yet led to large scale movements of Afghans across the region, let alone into Europe, UN officials estimate that half a million Afghans could flee the country by the end of the year alone. It is also likely that the alarming trends reported by MMC’s 4Mi enumerators, including an increasing reliance on smugglers, escalating costs, and increased protection risks, will also continue and increase as the current situation further unfolds.

In anticipation of potential onward movements of Afghans, neighboring governments and those in the EU brace themselves for a crisis. Through the release of the EU Action Plan responding to the events in Afghanistan, it is clear that the EU’s approach is primarily to keep Afghans within the region or at least away from European borders, with an additional 3 billion Euros allocated (on top of the already allocated 6 billion) under the EU Facility for Refugees to support refugees in Turkey and Turkey’s migration management capacity. Compared to 300 million Euros to support resettlement from Afghanistan and an additional 300 million Euros for humanitarian assistance in Afghanistan, the priorities are clear. And while history has shown us most Afghans will remain within the region in Iran and Pakistan and increasingly Turkey, the pressure on these countries is mounting. Regional neighbors of Afghanistan have already been hosting many Afghans for more than four decades, whilst simultaneously struggling with their own economic and political challenges.

While closed borders, pushbacks, increasing protection risks and the inflated costs of journeys may deter Afghans from reaching the EU in the short-term, durable solutions are desperately needed for the millions already displaced and those newly so, across the region. Without ensuring access to public services, education, employment, and documentation for displaced Afghans across the region, their safety and future prosperity are severely limited and the need for onward movements to countries including those within the EU will only increase.

Indeed, MMC’s 4Mi data from Turkey shows that many Afghans intend to move on. Among those interviewed in August 2021, only 22% indicated that Turkey was their intended final destination (to either live there or apply for asylum and wait for resettlement in the future). This is compared to 73% who reported that they intend to continue moving onwards to another destination, including to Europe, with Germany as the preferred destination. Another 5% mentioned that they have not decided on their final destination.

The country I want to reach is not very important. What is important is that I want to find a peaceful place and live there with my family and children. A place where my children are safe and I can work for their future.

4Mi respondent, 36 years old male, interviewed in Istanbul

Conclusion

Migration has long been a last-resort and lifeline for Afghans fleeing persecution, conflict, poverty, and environmental disaster. The current crisis unfolding in Afghanistan intersects with these long-established drivers of migration and displacement, forming an ecosystem of issues which many fear will lead to an unprecedented humanitarian crisis, mass displacement and increased migration within and beyond the region.

While initial responses from the international community to the events unfolding in August saw the evacuation of thousands of at-risk Afghans by air, more medium to longer-term policy responses from countries in the region and beyond have included the increasing securitization of borders and the ramping up of externalization measures to prevent the predicted onward movements from Afghanistan. These responses will only cause harm, forcing Afghans in vulnerable situations to embark on increasingly risky irregular journeys, or face being trapped in dangerous, precarious and life-threatening situations.

Strong commitments from various actors are desperately needed, including solidarity in action between the de facto government of Afghanistan, regional governments, the EU, and other Western states in order to facilitate safe passage for people whose only lifeline is migration. This includes providing regular, effective, and accessible migration and asylum pathways. Donor and host countries alike must also ramp up efforts to protect the rights of displaced Afghans throughout the region and beyond, sharing responsibility in order to adequately address the escalating needs. This includes, among other things, recalling commitments made under the Global Compact on Refugees and its guiding principles to ensure that Afghans seeking refuge can do so safely and host countries are supported accordingly.

[1] 4Mi is MMC’s flagship data collection initiative and offers a regular, standardized, quantitative and globalized system of collecting primary data on mixed migration flows via a network of trained community enumerators. While all 4Mi data collection in Afghanistan has temporarily ceased, MMC’s 4Mi enumerators continue to offer observations regarding the movement of people from locations in border areas across Afghanistan. 4Mi is also active in Turkey with Afghans on the move as of August 2021.